Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are a significant contributor to the phenomenon of global warming, acting like an invisible blanket that traps heat in the atmosphere. These gases arise from both natural and anthropogenic sources and play a crucial role in the Earth’s energy balance. Understanding the mechanics of how GHGs function is essential to grasping the larger narrative of climate change and its impacts.

At the core of the greenhouse effect is the interplay between solar energy, the Earth’s surface, and the atmosphere. Solar radiation penetrates the atmosphere and warms the Earth’s surface. Subsequently, the Earth radiates heat back into space as infrared energy. However, greenhouse gases absorb some of this infrared radiation, preventing it from escaping into the cosmos. This process, although natural and vital for sustaining life, is exacerbated by the increased concentration of GHGs due to human activities.

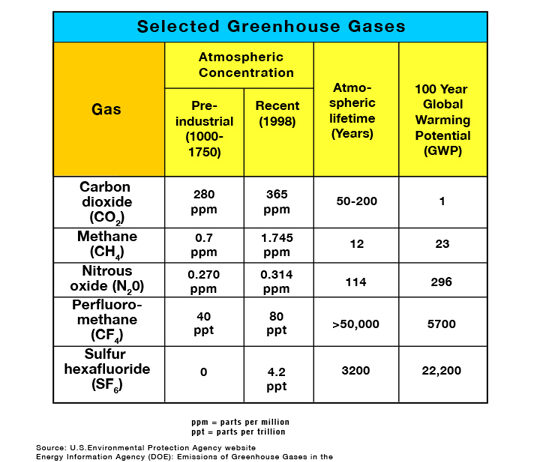

There are several key types of greenhouse gases, each with distinct properties and effects on global warming. Among the most significant are carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and fluorinated gases. Each of these gases has varying capacities for heat retention and contributes in unique ways to the greenhouse effect.

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

Carbon dioxide is the most prevalent greenhouse gas emitted by human activity, primarily through the combustion of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas. Deforestation also contributes to elevated CO₂ levels by reducing the number of trees available to absorb this gas. CO₂ has an atmospheric lifetime of centuries, meaning that once released, it persists for a long time, continuously influencing the climate. It is estimated that the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere has increased by over 40% since the pre-industrial era.

Methane (CH₄)

Methane is another potent greenhouse gas, with a global warming potential significantly greater than that of carbon dioxide—approximately 25 times more effective at trapping heat over a century. It is released during the decomposition of organic matter in anaerobic conditions, such as in wetlands and landfills, as well as from livestock digestion and certain agricultural practices. The atmospheric lifetime of methane is shorter than that of CO₂, around a decade, but its potency makes it a critical focus in efforts to mitigate climate change.

Nitrous Oxide (N₂O)

Nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas that is emitted during agricultural and industrial activities, as well as during the combustion of fossil fuels and solid waste. With a global warming potential approximately 298 times greater than CO₂ over a 100-year period, N₂O also has a dual effect; it is a significant ozone-depleting substance. Its prevalence in the atmosphere is largely attributable to the use of synthetic fertilizers, which release N₂O as they break down into soil.

Fluorinated Gases

Fluorinated gases encompass a variety of synthetic gases used primarily in industrial applications, refrigeration, and air conditioning. These include hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆). Although they are present in much smaller quantities in the atmosphere compared to CO₂, their global warming potentials can be thousands of times greater than CO₂. Their long atmospheric lifetimes, which can reach up to thousands of years, make them particularly concerning for future generations.

The Feedback Mechanisms

Greenhouse gases not only contribute to warming but also initiate feedback mechanisms that can escalate the rate of climate change. One such mechanism involves the melting of polar ice. As global temperatures rise, ice sheets and glaciers melt, reducing the reflective surface area and allowing for greater absorption of solar energy by the ocean and land. This process accelerates warming, leading to further ice melt in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Additionally, the thawing of permafrost releases stored carbon and methane, further exacerbating atmospheric concentrations of these gases. Such feedback loops illustrate the intricate and interlinked nature of climate systems, where the effects of one phenomenon can amplify another.

Global Impacts of GHG Emissions

The consequences of increased greenhouse gas emissions are pervasive and multifaceted. They include rising global temperatures, more frequent and severe weather events, shifts in ecosystem dynamics, and rising sea levels. Increased temperatures can lead to prolonged droughts and an uptick in wildfires, while excessive rainfall can result in catastrophic flooding events, disrupting communities and ecosystems alike.

Moreover, global warming affects agricultural productivity, threatening food security. Crops may struggle to adapt to changing climate conditions, requiring farmers to invest in new practices, technologies, and crops that can withstand the new normal. The economic implications of these necessary adaptations can strain both individual farmers and broader agricultural systems.

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies

Addressing the challenge of greenhouse gas emissions requires a multifaceted approach that incorporates both mitigation and adaptation strategies. Transitioning to renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, can significantly reduce reliance on fossil fuels and drive down CO₂ emissions. Enhancing energy efficiency in buildings and transportation can further decrease energy consumption.

Additionally, reforestation and afforestation efforts are critical in absorbing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Sustainable agricultural practices that minimize methane and nitrous oxide emissions can also contribute significantly to net reductions in greenhouse gases. Policy measures, such as implementing carbon pricing and regulatory frameworks, are instrumental in fostering these transitions.

In conclusion, greenhouse gases are the invisible heat trappers that significantly influence global warming. Understanding their mechanisms, sources, and the multifaceted impacts they have on our planet is crucial for implementing effective strategies to combat climate change. Collective action and informed policies are imperative to mitigate the adverse effects associated with these gases and to protect future generations from the challenges posed by global warming.