How do we know humans are causing global warming? It’s a question that invites both skepticism and curiosity. As the debate surrounding climate change intensifies, facts collide with myths, often leading to confusion. This article aims to demystify the empirical evidence underpinning the human contribution to global warming while addressing common misconceptions.

First, let’s consider the scientific consensus. Over 97% of climate scientists agree that human activities are a significant driver of climate change. This unity stems from extensive research, peer-reviewed studies, and the accumulation of robust data over decades. The unprecedented rate of temperature increase since the Industrial Revolution indicates a stark deviation from natural climatic variability. But how do we quantify and ascertain this? The key lies in understanding several critical aspects of climate science.

The greenhouse effect is fundamental to grasping how human actions influence global temperatures. The Earth’s atmosphere contains gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), which trap heat. This process maintains the planet’s temperature but has been drastically intensified due to human emissions, particularly from fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and industrial processes. Historical data reveals that CO2 levels are currently at their highest in 800,000 years. This surge is not a mere coincidence but rather a direct consequence of anthropogenic activities.

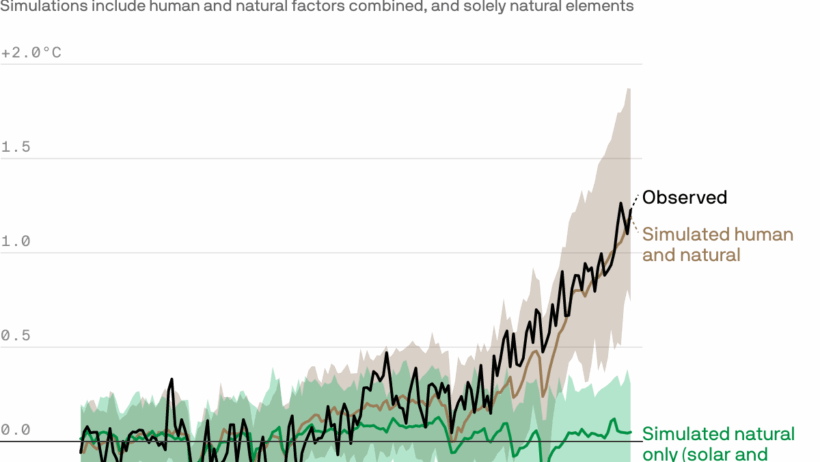

One might wonder: Are there any natural processes contributing to this increase? The answer is nuanced. While natural factors such as volcanic eruptions, solar irradiance, and ocean currents do influence the climate, their contributions in recent decades have been minimal compared to the impacts of human activity. For example, a significant volcanic eruption may cool the planet temporarily, but it pales in comparison to the sustained warming produced by CO2 emissions. Hence, while natural variability exists, it cannot account for the rapid changes witnessed today.

Next, we must address attribution studies, which use advanced climate models to determine the likelihood that observed changes are due to human actions versus natural variability. These studies consistently demonstrate that the warming trend since the mid-20th century is highly unlikely to occur without human influence. Through simulations and statistical analyses, scientists can isolate the effects of greenhouse gases from natural factors, bolstering the argument for human-induced climate change.

Now let’s confront some prevalent myths that muddle the discourse. One common misconception is that climate change is just a natural cycle. This oversimplification ignores the intricate role humans play in accelerating these cycles. Next, there’s the notion that weather fluctuations equate to climate change. Weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions, while climate encompasses long-term trends. The distinction is crucial; a cold winter does not invalidate the overarching trend of global warming.

The role of data in this discussion cannot be overstated. Organizations such as NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have amassed extensive datasets documenting temperature changes, ice core samples, sea level rise, and atmospheric composition. For instance, melting glaciers and diminishing Arctic sea ice are tangible indicators of rising global temperatures. The alarming rate at which polar ice caps are receding highlights the urgency of the situation—evidence that is irrefutable and requires our immediate attention.

If you’re pondering the implications for future generations, consider this: unchecked global warming poses existential threats, such as increased extreme weather events, rising seas, and devastating impacts on biodiversity. These consequences are not merely hypothetical scenarios; they are currently manifesting worldwide. Imagining a world where rising temperatures exacerbate resource scarcity or displace populations is not an exaggeration but a genuine concern.

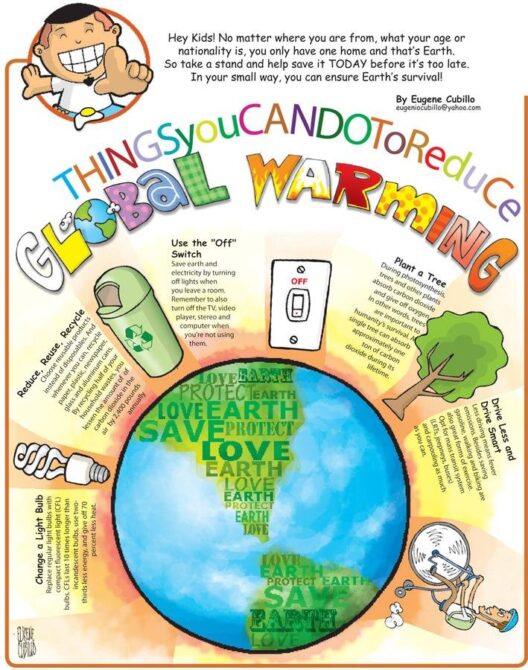

Another oft-cited argument is that climate change is too complex for individuals to influence. While it’s true that the intricacies of climate science can be overwhelming, personal and collective actions can and do create significant change. Transitioning to renewable energy, advocating for sustainable practices, and supporting policies aimed at reducing carbon footprints are powerful avenues for driving transformation. Every choice—whether it’s reducing meat consumption, using public transport, or advocating for stringent environmental protections—contributes to the collective response needed to combat climate change.

Furthermore, the overwhelming data paints a vivid picture of the economic implications of inaction. The costs associated with climate-related disasters, health problems due to air pollution, and loss of biodiversity could far exceed the investments required for sustainable practices and renewable resources. Economists and environmentalists alike emphasize that addressing climate change through proactive strategies could yield not only environmental benefits but also economic rewards.

Engagement with climate change is not solely an obligation; it’s an opportunity for innovation and leadership. A dedicated focus on sustainability can foster new industries, create jobs, and enhance community resilience against environmental uncertainties. By embracing change rather than resisting it, society can pave the way for a sustainable future, harnessing human ingenuity to combat the challenges of global warming.

In conclusion, the evidence supporting human-induced climate change is substantial and compelling. By understanding the science, navigating through common myths, and recognizing the personal and societal implications of our actions, we can collectively address this existential challenge. The questions surrounding climate change are not just academic; they involve our future and that of the planet. It’s time to step up, acknowledge the facts, and engage in the solutions. The planet is not waiting, and neither should we.