Energy conservation is a fundamental principle in the realm of physics. It stipulates that in an isolated system, the total energy remains constant over time, although it may change forms. Understanding how to determine if energy is conserved is crucial for various applications, from analyzing mechanical systems to comprehending thermodynamic behaviors. This discussion aims to provide a practical approach to calculating energy conservation, replete with relevant examples and contexts.

At its core, energy conservation can be illustrated through a range of simplistic observations. A pertinent example involves a swinging pendulum. At its apex, the pendulum possesses maximum potential energy, converted fully to kinetic energy at the lowest point of its swing. Such transformations exemplify the interchangeability of energy forms, a vital aspect of the conservation principle.

To calculate whether energy is conserved, one must first define the system under observation. An isolated system, for our purposes, is one free from external influences such as friction or air resistance. If external forces are present, they must be accounted for as they can dissipate energy in the form of heat or sound. Consequently, selecting the appropriate boundaries for the system is imperative when engaging in calculations.

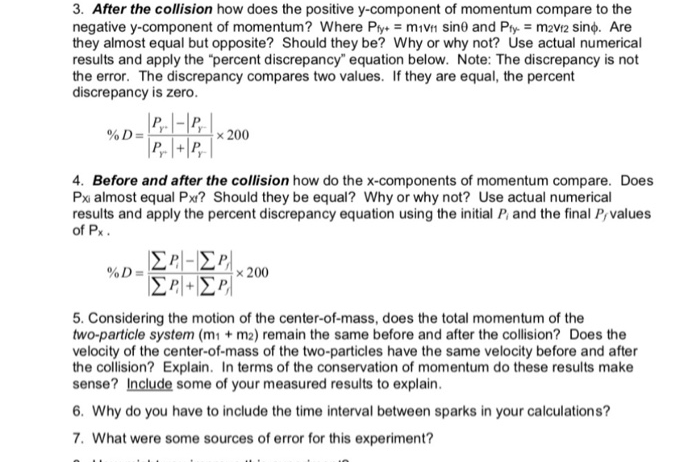

The first step in determining energy conservation is identifying the types of energy involved. The primary forms of energy that may enter into calculations include:

- Kinetic Energy (KE): The energy associated with the motion of an object, quantified by the formula KE = 0.5 * m * v², where m denotes mass and v indicates velocity.

- Potential Energy (PE): The energy stored due to an object’s position or arrangement, particularly relevant in gravitational contexts, defined by PE = m * g * h, with g as the gravitational constant and h referring to height above a reference point.

- Thermal Energy: Energy related to the temperature of an object, often imperceptible during basic mechanical interactions but significant in thermal systems.

- Elastic Energy: Energy stored in objects that can stretch or compress, such as springs, represented through the formula EE = 0.5 * k * x², where k is the spring constant and x is the distance compressed or stretched.

Once energy types are identified, one can perform calculations. For instance, consider a roller coaster at the peak of a hill converting potential energy into kinetic energy as it descends. At the highest point, the potential energy amounts to PE = m * g * h. As the ride drops, this potential energy decreases while kinetic energy increases, contributing to the overall conservation of energy principle. At any point, the total mechanical energy (the sum of kinetic and potential energy) should remain constant:

KE + PE = Constant

To illustrate this concept, let’s perform a hypothetical calculation. Assume a roller coaster car with a mass of 500 kg is situated at a height of 40 meters (m). To find the potential energy at that height:

PE = m * g * h = 500 kg * 9.81 m/s² * 40 m = 196200 J

While descending, if the car reaches a speed of 20 m/s at a height of 10 m, its kinetic energy can be calculated:

KE = 0.5 * m * v² = 0.5 * 500 kg * (20 m/s)² = 100000 J

The potential energy at a height of 10 m is:

PE = m * g * h = 500 kg * 9.81 m/s² * 10 m = 49050 J

The total mechanical energy at this point is:

KE + PE = 100000 J + 49050 J = 149050 J

As one can observe, the total energy at the initial height (196200 J) and the energy at the current height (149050 J) do not match, highlighting energy dissipation likely due to friction, air resistance, or other forces not accounted for initially.

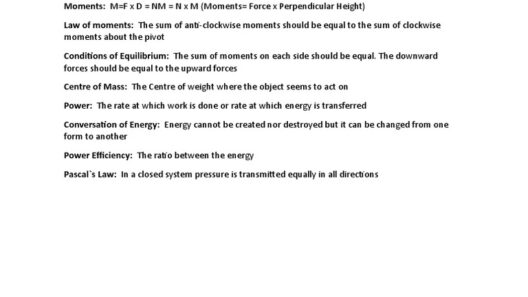

When discussing energy conservation calculations, thermodynamic systems present an additional layer of complexity. The first law of thermodynamics governs these systems, revealing that energy cannot be created or destroyed—only transformed. This law becomes increasingly pertinent when heat exchanges or work done are involved. When analyzing a boiling kettle of water, one ought to consider both the thermal energy input from the heat source and the eventual heat loss to the surrounding air.

To ascertain if energy is conserved in a thermodynamic system, one must employ the equation:

ΔU = Q – W

Here, ΔU represents the change in internal energy, Q is the heat added to the system, and W is the work done by the system.

This practical approach to calculating energy conservation serves as not only a technical exercise but also an invitation to a deeper comprehension of the universe. Energy transformation is omnipresent and underpins numerous phenomena, inspiring fascination and inquiry. By adhering to systematic calculations and principles, one can grasp the profound interconnectedness of energy forms, promoting a better understanding of natural laws and their implications.

In summation, determining if energy is conserved necessitates meticulous identification of energy forms, accurate calculations considering both isolated and thermodynamic systems, and a thoughtful consideration of external forces. As our world grapples with the impacts of climate change and energy sustainability, understanding these principles becomes paramount in innovating solutions and fostering responsible energy usage.