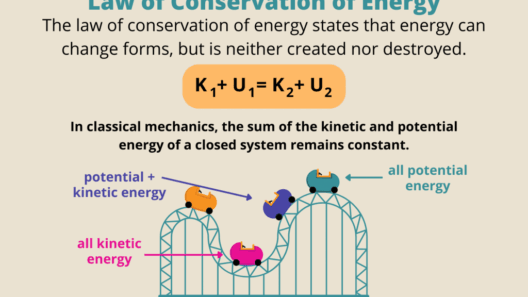

Have you ever pondered how a simple ball thrown upwards eventually falls back down, or how fast a roller coaster must move at the pinnacle of its track? Understanding the velocity of moving objects often necessitates a grasp of the conservation of energy principle. This fundamental concept allows us to connect various forms of energy and derive important motion characteristics. Let’s embark on a thorough exploration of how to find velocity using conservation of energy, specifically focusing on kinetic and potential energy forms, mathematical approaches, and practical applications.

The principle of conservation of energy states that energy in a closed system remains constant; it cannot be created or destroyed, merely transformed from one form to another. In the realm of mechanics, we typically deal with kinetic energy (KE) and gravitational potential energy (PE). Kinetic energy is the energy of motion and is quantified by the equation:

KE = ½ mv²

In this equation, m represents mass and v denotes velocity. Potential energy, particularly in the gravitational context, is given by:

PE = mgh

where g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.81 m/s² on Earth), and h is the height above a reference point.

In practical scenarios, consider a situation where an object is dropped from a height or thrown vertically. The interplay between potential energy and kinetic energy provides an insightful avenue to calculate velocity. At the object’s original height, the energy possessed is solely potential energy. As it descends, this energy diminishes, converting to kinetic energy until reaching the ground, where potential energy is zero.

Let’s break down the pivotal steps and math involved:

- Initial Energy Calculation: At the highest point, the object has maximum potential energy. Calculate this by applying the potential energy formula, substituting the mass and the height.

- Final Energy State: Upon reaching the ground, all potential energy converts to kinetic energy. Setting the potential energy equal to the kinetic energy, we have:

mgh = ½ mv²

Notice that the mass m is present on both sides of the equation, allowing it to be canceled out. This simplification promotes a more generalized solution for finding velocity:

v = √(2gh)

This expression demonstrates that the object’s velocity upon impact is directly influenced by the height from which it was dropped. The greater the height, the more pronounced the velocity at the moment of contact with the ground.

With the theoretical framework firmly established, let’s pivot towards a tangible application of these principles. Suppose you have a ball weighing 1 kg, dropped from a height of 5 meters. Calculating its impact velocity demands substituting values into the derived formula:

v = √(2 * 9.81 m/s² * 5 m) = √(98.1 m²/s²) ≈ 9.9 m/s

Therefore, the ball hits the ground with an approximate velocity of 9.9 meters per second. This calculation only scratches the surface, opening the door to a diverse array of applications, from engineering pursuits to sports physics.

Moreover, velocity determination through energy conservation is not confined to vertical motion alone. In horizontal or projectile motion, the same principles apply. For instance, consider a roller coaster on a hill: as it ascends, energy conservation principles govern its dynamics. At the highest point, the coaster’s energy is mainly potential. As the coaster dives down, that potential energy gradually converts to kinetic energy, accelerating the ride.

One common challenge arises when dealing with energy losses due to friction and air resistance. These forces oppose motion and diminish the amount of mechanical energy available. Thus, the formula incorporates these losses to present a more realistic depiction of energy conversion:

KE_initial + PE_initial – Work_done = KE_final + PE_final

Here, Work_done signifies energy lost to friction or air resistance. This often necessitates experimentation and empirical data collection to accurately assess the coefficients of friction involved.

Furthermore, let’s delve into the practical aspect of velocity determination in real-world phenomena. Spaces like amusement parks, sports arenas, and educational laboratories provide excellent opportunities to analyze conservation of energy in motion. Accurately measuring the height of an amusement park ride, or understanding the energy dynamics during athletic activities, is instrumental in physics and engineering.

Consequently, while the principles of energy conservation may seem straightforward, their intricacies can pose significant challenges. Engaging with these concepts encourages critical thinking and enhances comprehension of the natural laws governing the universe. As our understanding deepens, we become better equipped to address real-world issues, from improving safety standards in transportation to harnessing renewable energy solutions based on kinetic movement.

In summation, the relationship between velocity and conservation of energy unveils a profound understanding of motion and energy’s transformative powers. Whether through theoretical calculations or empirical examinations, mastering these concepts not only enriches one’s knowledge base but also fosters innovation and creativity within scientific fields. Before closing, contemplate this: how might we apply our insights into energy conservation to develop more sustainable technologies and practices in our daily lives?