Inelastic collisions are a fascinating phenomenon characterized by a loss of kinetic energy that occurs during the impact of colliding objects. To understand the mechanics of these interactions, we must delve into the essential principles governing momentum and kinetic energy. Here, we’ll explore their fundamental differences, the conservation laws that apply, and how inelastic collisions manifest in real-world scenarios.

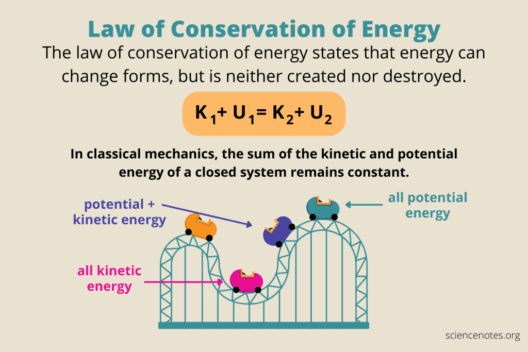

First, it is crucial to define the terms involved. Momentum is defined as the quantity of motion an object possesses, mathematically expressed as the product of mass and velocity (p = mv). This vector quantity embodies both magnitude and direction, making it integral in the analysis of colliding bodies. On the other hand, kinetic energy, which quantifies the energy possessed by an object due to its motion, is given by the equation KE = 1/2 mv². Unlike momentum, kinetic energy is a scalar quantity, meaning it has no direction.

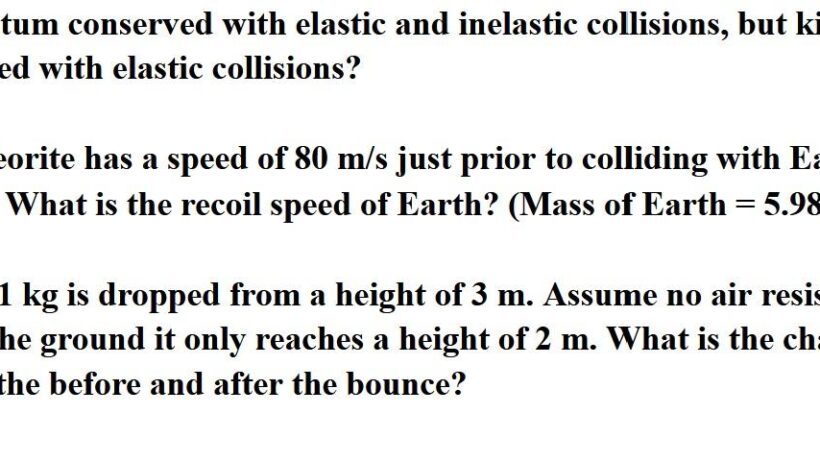

One of the cornerstones of physics is the principle of conservation. In isolated systems, both momentum and energy behaviors differ widely during collisions. In perfectly elastic collisions, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved. However, in the case of elastic collisions, one cannot make the same assertion regarding kinetic energy. A hallmark of inelastic collisions is that while momentum is conserved, kinetic energy is not.

Let’s elucidate this with an example: Consider two bumper cars colliding at an amusement park. When these cars collide inelastically, they may crumple together, illustrating the concept of inelastic deformation. Post-collision, the two cars may move together at a shared velocity, signifying a combined mass with a corresponding momentum. However, their individual kinetic energies prior to the collision, summed together, will diminish due to energy dissipation, likely transformed into heat or sound energy.

The conservation of momentum can be expressed mathematically. If two objects, A and B, collide and stick together, the formula before collision can be represented as:

mAvA,i + mBvB,i = (mA + mB)vfIn this equation, m represents mass, v denotes velocity, and subscripts indicate initial (i) or final (f) conditions. This equation governs the conservation of momentum, confirming that the total momentum before the collision is equivalent to the total momentum after.

Conversely, kinetic energy will appear different post-collision, a situation that can be represented as:

KEi ≠ KEfHere, “KEi” indicates the initial kinetic energy, while “KEf” represents the final kinetic energy. The inequality implies that some kinetic energy has been transformed into other energy types like thermal energy, sound, or internal energy—thus demonstrating a lack of conservation of kinetic energy.

To further delineate this concept, consider the coefficient of restitution, a measure reflecting the elasticity of a collision. Defined as the ratio of relative speeds after and before an event, it quantitatively assesses the elasticity—ranging from 0 (perfectly inelastic) to 1 (perfectly elastic). A perfectly inelastic collision, visually evident in a scenario such as two blobs of clay merging upon impact, results in maximum deformation—indicating near total kinetic energy loss.

Inelastic collisions can be categorized upon differing contexts. A perfectly inelastic collision embodies the extreme end of the spectrum, where two masses stick together post-collision. A common real-world example is a car crash, where vehicles may crumple and come to rest due to significant energy loss after impact.

Conversely, a partially inelastic collision sees some kinetic energy conserved, manifesting in cases like sports, where a basketball hitting the floor retains some energy to bounce back, though undeniably not to its original height. Therefore, it oscillates between energy losses and conservation, firmly illustrating the interplay between momentum conservation alongside energy transformation.

Understanding inelastic collisions is not merely academic; it has practical implications across various scientific fields and applications. Engineers, for instance, apply these principles to design safer automotive structures, ensuring that cars absorb maximum impact energy during crashes. Hence, through proper engineering, kinetic energy is diverted away from passengers, prioritizing safety.

Moreover, inelastic collisions are pervasive in daily life. From accidents that cause property damage to sports events where athletes collide, the principles governing these events hold true. Thus, even without a stringent focus on physics, the effects of inelastic collisions are widespread and perceptible.

In summary, while analyzing inelastic collisions, it becomes patently clear that momentum is a conserved quantity, while kinetic energy is not. The implications of these findings reach far beyond theoretical physics, impacting engineering, safety mechanisms, and everyday occurrences. Understanding these principles not only enriches one’s grasp of physical laws but also underscores the real-world consequences of energy transformation during inelastic impacts. The examination of such collisions illuminates the intricate dance between theory and practical application, bridging a critical gap in understanding human-made and natural systems alike.