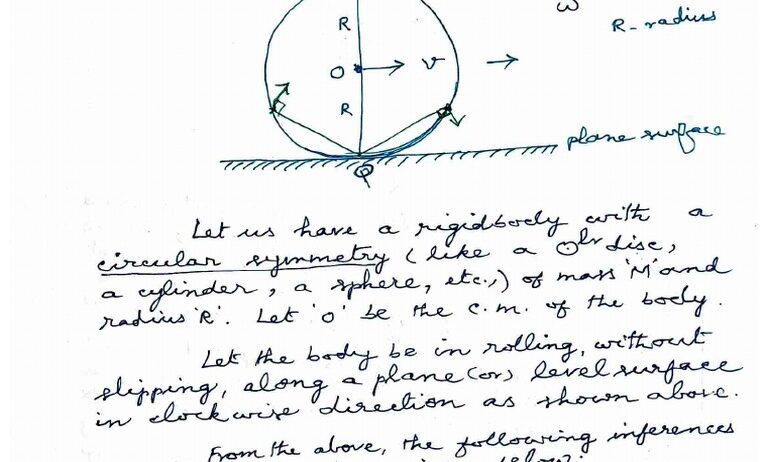

When exploring the phenomenon of rolling motion, particularly the behavior of a solid body rolling without slipping, it is imperative to understand the fundamental principles governing energy conservation. In the context of classical mechanics, the question arises: is energy conserved during this process? To answer this, we must delve into the dynamics of rolling motion and analyze the various forms of energy involved.

Rolling without slipping occurs when a body, such as a wheel or a sphere, rotates about its axis while maintaining contact with a surface. This contact ensures that the point of the body in contact with the surface is momentarily at rest, allowing it to roll smoothly without sliding. The key forms of energy present during this motion are translational kinetic energy, rotational kinetic energy, and potential energy. A comprehensive examination of these energy forms aids in delineating whether energy is conserved.

Translational kinetic energy ((KE_{trans})) is the energy associated with the movement of the center of mass of the rolling object. It is mathematically represented as:

KE_{trans} = frac{1}{2} mv^2where (m) is the mass of the body and (v) is the linear velocity of its center of mass. Conversely, the rotational kinetic energy ((KE_{rot})) pertains to the energy due to the body’s rotation about its axis, expressed as:

KE_{rot} = frac{1}{2} I omega^2In this equation, (I) signifies the moment of inertia of the body, and (omega) represents the angular velocity. For rolling motion without slipping, a crucial relationship exists between the linear velocity (v) and the angular velocity (omega), defined by:

v = Romegawhere (R) is the radius of the rolling body. This relationship indicates that as a solid object rolls, its translational and rotational motions are intricately connected. Consequently, the total mechanical energy ((E_{total})) in an ideal system—absent of external forces, frictional losses, or air resistance—can be expressed as the sum of translational and rotational kinetic energies alongside potential energy ((PE)):

E_{total} = KE_{trans} + KE_{rot} + PEAs long as no non-conservative forces are acting upon the system, total mechanical energy remains constant, advocating the principle of energy conservation. However, under practical conditions, one must consider energy dissipation due to factors such as friction or deformation, which can potentially complicate the conservation assertions.

To illustrate energy conservation in the absence of slipping, consider a solid sphere descending an incline. As the sphere rolls down, its potential energy is converted into both translational and rotational kinetic energy. The gravitational force acting on the sphere induces a decrease in potential energy, given by:

PE = mghwhere (h) signifies the height of the sphere above a reference point. As the sphere descends, its velocity increases, resulting in an augmented translational kinetic energy, while simultaneously, its rotational speed escalates, enhancing rotational kinetic energy.

By applying the principle of conservation of energy in this scenario, we can deduce that the loss of potential energy translates into a sum of gains in both translational and rotational kinetic energies:

mgh = frac{1}{2} mv^2 + frac{1}{2} I omega^2This equation can be simplified by substituting the moment of inertia of a solid sphere, which is (frac{2}{5} mR^2). Through this simplification, it becomes apparent that the energy is indeed conserved throughout the rolling motion. Moreover, it is imperative to highlight that the conversion is seamless, predicated upon the absence of slipping, which would induce additional energy losses.

Rolling without slipping is thus a paradigm of mechanical efficiency, wherein a body deftly transitions its energy from one form to another without a net loss. The presence of frictional force at the point of contact is not detrimental; instead, it is essential for maintaining the rolling condition. Friction here acts as a static force, preventing slipping and facilitating the exchange of energy forms effectively.

On the contrary, rolling with slipping introduces more complexity. In this scenario, part of the energy is dissipated as heat due to the kinetic friction motions between the rolling body and the surface. Under these conditions, the conservation of energy principle becomes convoluted, as not all potential energy is converted into kinetic energy. Energy losses manifest through non-conservative forces, implying that the system’s mechanical energy decreases.

In conclusion, the conservation of energy during rolling without slipping is upheld in ideal circumstances, where the system avoids external disturbances and frictional losses. The mechanical energy is effectively transferred between potential, translational kinetic, and rotational kinetic states through a harmonious interplay of forces. Understanding these dynamics allows one to appreciate the nuanced principles governing rolling motion in various applications, from vehicles to machinery, further illuminating how energy conservation remains a cornerstone of physic phenomena.