In the realm of physics, understanding the concept of energy conservation is fundamental. Energy conservation is a principle that states energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only change forms. This principle holds across various physical interactions, including collisions. However, the intricacies of energy conservation can vary significantly depending on the type of collision involved. This article delves into the nuances of energy conservation in collisions, particularly focusing on elastic, inelastic, and perfectly inelastic collisions.

First, it is essential to categorize collisions into two primary types: elastic and inelastic. Each category is characterized by how kinetic energy is treated during the interaction.

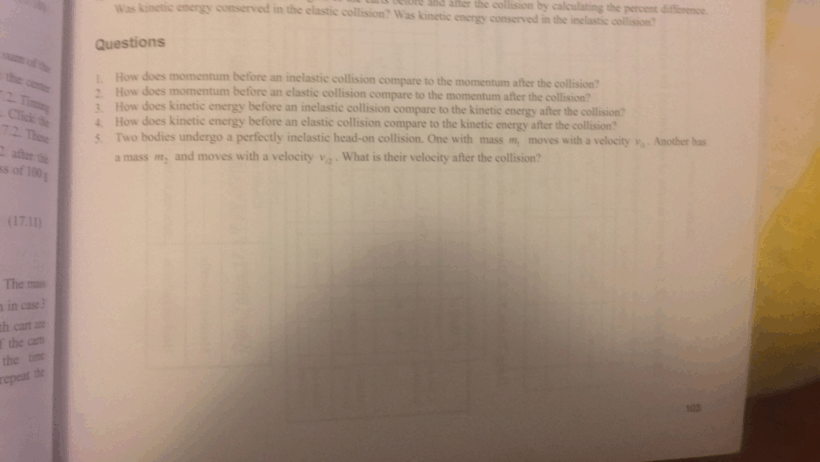

An elastic collision is defined as one where both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved. In these interactions, the objects involved collide and then separate, with the total kinetic energy before the collision being equal to the total kinetic energy after the collision. A familiar example of elastic collisions can be found in the behavior of billiard balls. When one billiard ball strikes another, they exchange momentum and kinetic energy, but the total remains constant, demonstrating the principle of conservation in action.

In examining elastic collisions further, physics reveals an alluring complexity. The conditions for an elastic collision necessitate perfectly rigid bodies and an environment where energy is not lost to sound, heat, or deformation. Such conditions rarely exist in everyday life but are approximated in the realm of atomic and subatomic particles. The collision of gas molecules, for instance, trends toward an elastic nature at certain temperatures and pressures, making it a captivating study in thermodynamics.

Contrariwise, inelastic collisions provide a contrasting perspective on energy conservation. In an inelastic collision, while momentum remains conserved, kinetic energy does not. This lack of energy conservation can be attributed to the transformation of kinetic energy into other forms of energy, such as thermal energy, sound, or even energy associated with deformation. A quintessential example of an inelastic collision is a car crash. In such an event, the colliding cars crumple upon impact. The kinetic energy originally present in the vehicles is partly transformed into internal energy, manifesting as heat and light, thereby illustrating the principle that energy, while conserved in totality, can be redistributed among different forms.

Perfectly inelastic collisions are a specific subset of inelastic collisions, wherein the colliding objects stick together post-collision. This scenario results in the maximum possible kinetic energy loss consistent with momentum conservation. A common example of this type is when two clay masses collide and stick together, moving as one composite object afterward. Despite the significant loss in kinetic energy, overall momentum remains conserved. These types of collisions evoke deeper reasoning; they serve as a poignant reminder of how physical interactions underpin dynamic systems, despite the apparent energy loss in kinetic form.

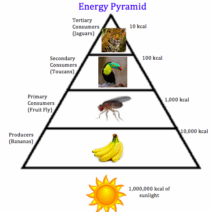

One may ponder why our fascination with collisions goes beyond mere observation. The study of collisions and energy conservation probes into core principles of physics that govern the universe: the laws of motion, thermodynamic equilibrium, and the bidirectional flow of energy through various systems. Recognizing whether energy is conserved or transformed during collisions can illuminate broader ecological implications, particularly in fields such as sustainable energy and conservation. For instance, understanding energy transfer in vehicles has leading implications for improving fuel efficiency and lowering emissions—key factors in addressing environmental concerns.

The configurations of different collisions remind us that each scenario carries unique implications. The calculation of energy conservation in each type of collision can provide insights into the potential transformations of energy during interactions. Analyzing these interactions requires a thorough understanding of momentum and kinetic energy, alongside the foundational equations of physics: p = mv (momentum), and for kinetic energy, K.E. = 0.5mv².

When studying real-world applications, environmental advocates emphasize the importance of energy conservation in mechanical systems. For example, in industrial processes and energy generation, the efficiency of collisions and material interactions can significantly affect the overall conservation of energy. Reducing energy lost to inelastic collisions—such as friction and heat—is tantamount to promoting efficiency and sustainability.

On a societal level, fostering awareness about the conservation of energy during collisions in transportation can motivate individuals and communities to adopt more sustainable practices. Technologies that harness and optimize energy transfer during collisions, such as regenerative braking in electric and hybrid vehicles, showcase how understanding physics can drive innovation that aligns with environmental goals.

In conclusion, the exploration of whether energy is conserved in different types of collisions reveals a tapestry of physical principles that are both fascinating and profound. From elastic collisions showcasing energy conservation to inelastic collisions that reveal energy’s transformative capabilities, the physics of collisions serves as a microcosm for broader discussions on sustainability and environmental responsibility. As we continue to probe deeper into these principles, we gain not only knowledge but also responsibility in applying this understanding towards a more sustainable future.