Imagine a game of billiards, where each strike of the cue ball sends it ricocheting off its counterparts, altering their trajectories and velocities. This scenario sparks an intriguing question: is kinetic energy conserved during a partially elastic collision? To navigate this concept, we must first unpack the principles behind mechanical collisions in physics.

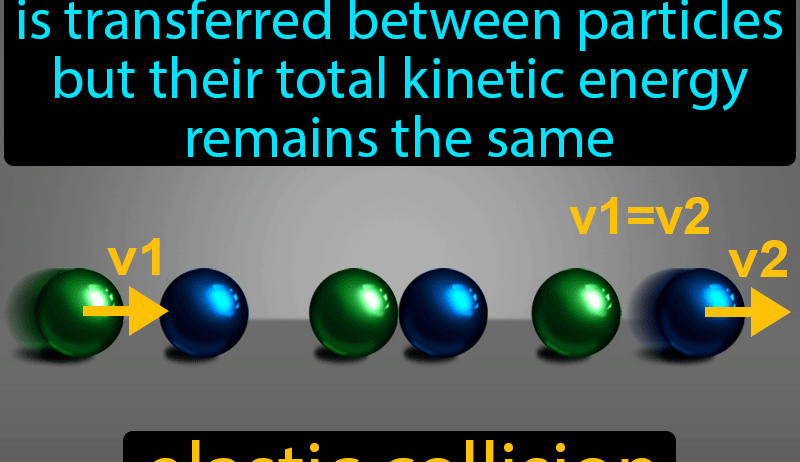

Collisions can be broadly classified into two categories: elastic and inelastic. In an elastic collision, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved. This occurs infrequently in real-world applications but can be approximated using atomic and subatomic particles, where collisions exhibit minimal energy transformation. Conversely, inelastic collisions are characterized by the absence of kinetic energy conservation; instead, some energy is transformed into other forms such as thermal energy, sound, or deformation. An exemplary case is a car crash, where vehicles crumple upon impact, leading to a significant loss of kinetic energy.

So, where does a partially elastic collision fit into this framework? It represents a middle ground. In a partially elastic collision, momentum is conserved, as it is in all collisions, but kinetic energy is not fully retained. Some fraction of kinetic energy is dissipated, while a portion remains as kinetic energy post-collision. Therefore, while one can assert momentum conservation in all types of collisions, the conservation of kinetic energy remains contingent upon the nature of the collision. This duality raises further intrigue as we explore how this interaction unfolds.

One might pose the question: under what circumstances might kinetic energy be conserved in a partially elastic collision? To dissect this, we must consider the properties of the objects involved. Take, for example, two identical spheres colliding with each other. In a perfectly elastic scenario, these spheres bounce off one another, retaining their original velocities. Yet, if we introduce the property of partial elasticity, perhaps through a deformation of the spheres upon collision, the post-collision kinetic energies would be less than those prior to impact, but not entirely lost. Both objects experience some deformation, leading to energy conversion into other forms, yet a fraction remains in the system as observable kinetic energy.

Additionally, the nature of the materials can dictate the specifics of energy conservation. For instance, when two rubber balls collide, they can retain much of their kinetic energy, demonstrating closer alignment to elastic behavior. However, even the most resilient materials will experience some deformation, indicating that complete energy conservation is an impractical notion. Each collision provides invaluable data, leading us to ponder how different materials and conditions could affect energy retention.

The mathematical framework defining kinetic energy is represented by the equation KE = 1/2 mv², where ‘m’ is mass and ‘v’ is velocity. This formulation indicates that even a minor alteration in velocity due to deformation can lead to a substantial loss in kinetic energy. For example, two objects of differing masses colliding will result in each experiencing force and acceleration in varying degrees, subsequently affecting their velocities. This behavior becomes increasingly complex when additional variables, such as friction and impulse, are considered. This complexity further illustrates the multifaceted nature of energy conversion during collisions.

Furthermore, the implications of partially elastic collisions extend beyond the realm of theoretical physics; they permeate into various real-world applications. Understanding partial elasticity is crucial in the design of safety features in automobiles, sporting equipment, and any system reliant on energy absorption, such as crumple zones in crash safety. The balance between conserving kinetic energy and absorbing it to protect occupants illustrates a tangible application of these physical principles.

Delving deeper into the implications, consider a playful experiment: drop a superball onto a concrete surface, and observe its bounce. The ball demonstrates partial elasticity; it retains a significant portion of its kinetic energy, bouncing back, albeit at a lower height than it was dropped from. This experience can easily parallel our question of whether kinetic energy is conserved. As the ball interacts with the concrete, it compresses upon impact, illustrating energy transformation. While it retains enough kinetic energy for a bounce, the measure of energy loss through sound and heat becomes evident as it oscillates before coming to rest.

As we juxtapose theoretical to practical notions, it becomes clear that while kinetic energy may not be conserved in totality during a partially elastic collision, it does remain in part. Such distinctions carry crucial weight in both academic arenas and practical engineering designs. The significance of embodying both the theoretical model and experimental findings plays a pivotal role in our evolving understanding of collision dynamics.

In conclusion, a partially elastic collision embodies the delicate interplay between kinetic energy and momentum conservation. It challenges our assumptions and invites further inquiry into the conditions that influence energy transformation. One is left to ponder how various collisions govern our everyday experiences, emphasizing that our understanding of the physical world is as layered and complex as the interactions we observe. Every collision tells a story of energy distribution, and as we probe deeper into these interactions, we may uncover myriad opportunities to enhance efficiency and safety across numerous spheres of our life.