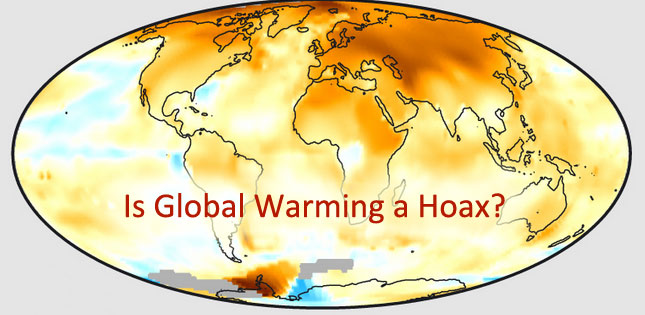

In recent years, the discussion around climate change has become more complex and multifaceted than many might have anticipated. Among the various narratives that surface frequently, one particularly controversial question arises: “Is less carbon dioxide worse?” While it may at first seem counterintuitive to argue against reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, unpacking this assertion reveals a more nuanced understanding of our planet’s environmental dynamics.

To explore this assertion, one must first recognize that carbon dioxide plays a critical role in the Earth’s atmospheric processes. As a greenhouse gas, CO2 is pivotal in maintaining the planet’s temperature; it absorbs infrared radiation, re-radiating heat and thereby preventing the Earth from succumbing to the deep freeze of space. In a certain context, a low concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere could lead to a disastrous cooling effect, disrupting ecosystems and agricultural productivity.

At its core, the argument surrounding whether less CO2 could be detrimental hinges upon the delicate balance of greenhouse gases. Advocates of the notion that less could be worse often refer to periods in Earth’s history when CO2 levels were significantly lower than today. During these epochs, such as the Permian Period, the planet experienced profound extinctions due largely to global cooling. This perspective posits that while current levels of CO2—driven largely by anthropogenic activities—are contributing to climate change, an abrupt and excessive reduction could have unforeseen consequences.

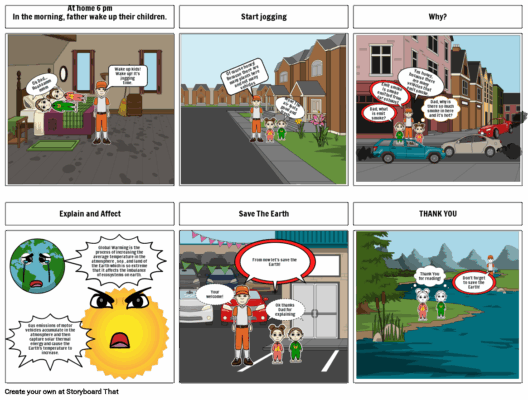

One of the key elements to consider is the relationship between CO2 levels and plant growth. Photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert carbon dioxide into oxygen and glucose, is fundamentally dependent on the availability of CO2. Higher concentrations can stimulate growth, particularly in arid regions where water availability is limited. Enhanced plant growth can lead to a more robust biomass, which in turn can promote biodiversity and improve soil health. Conversely, excessive reductions in CO2 could stunt plant growth, adversely affecting both food supply and ecological balance.

Similarly, aquatic ecosystems also exhibit a sensitivity to changes in CO2 levels. Marine phytoplankton, the foundation of oceanic food webs, thrive on CO2. Any abrupt decrease in available carbon dioxide could hinder their growth and reproduction. This has cascading effects up the food chain, threatening the myriad species, from krill to larger fish populations that rely on these microorganisms as a primary food source. The intricated web of interdependency within aquatic habitats illustrates the intricate relationships that exist in our biosphere, revealing that CO2, while contributing to climate change, also serves a fundamental role in health and sustainability.

Moreover, the argument that less carbon dioxide could be worse also opens a dialogue on the technological and policy-driven responses to climate change. There is a distinction to be made between sustainable practices aimed at decreasing greenhouse gas emissions and unregulated, rapid decarbonization efforts. The latter could inadvertently yield negative environmental impacts, resulting in sudden shifts in climate patterns that are damaging to both human and ecological health.

Critics of the prevailing narrative often highlight the importance of adaptation and mitigation strategies that target emissions reductions while also fostering resilience in ecosystems. This careful balancing act necessitates integrated approaches that consider not only the reduction of CO2 but also the safeguarding of natural systems that depend on a stable climate and atmospheric conditions.

Consider the implications of geoengineering solutions, which have gained traction in discussions on combatting climate change. Many of these proposed interventions focus on manipulating atmospheric components to directly absorb CO2. While well-meaning, such drastic measures could lead to unintended consequences on local and global scales. History teaches us that attempts to control natural systems often result in complex, unpredictable outcomes. Thus, the mantra of “more is better” may not apply straightforwardly to CO2 levels and their associated effects.

The conundrum arises—are we truly prepared to navigate the delicate interplay between preventing further warming and the catastrophic consequences of excessive decarbonization? It is essential to stress that nothing should dilute the urgency of addressing climate change. Still, it is equally critical to recognize that CO2 is not inherently villainous. Instead, it exists as part of a larger environmental equilibrium that we have yet to fully understand.

In grappling with this topic, it becomes evident that the key lies in fostering broader awareness of the implications of significant changes to CO2 levels. Education around this subject must challenge simplistic narratives, leading society toward more informed conversations around climate action. By viewing CO2 through a multidimensional lens, discussions can shift from polarized extremes to consideration of holistic, ecologically sound strategies.

Ultimately, the question “Is less carbon dioxide worse?” serves as a potent reminder of the intricacies of climate change. The conversation must evolve beyond categorical assertions, delving into the labyrinthine relationships that define our planet’s ecosystems. As environmental stewards, it is incumbent upon us to foster dialogues that embrace complexity, advocate for responsible actions, and commit to an informed, balanced approach towards mitigating climate impacts while recognizing the role of CO2 in our world.