Japan, an archipelago nestled in the eastern Pacific Ocean, is a nation characterized by its diverse and intricate climate zones. These zones are deeply affected by the country’s unique geography, which features a multitude of islands and mountainous terrains, alongside the influence of monsoonal patterns. This article will explore the various climate regions across Japan, delving into the nuances that distinguish them and examining their impact on both the environment and the lifestyle of the Japanese people.

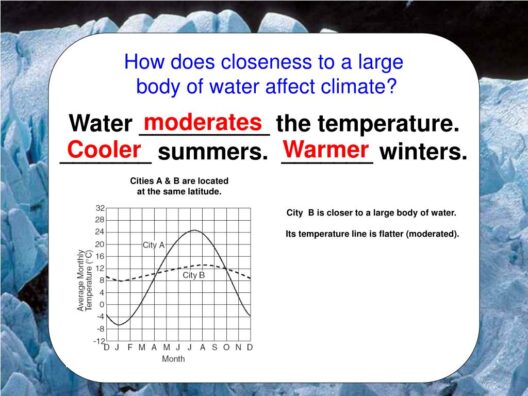

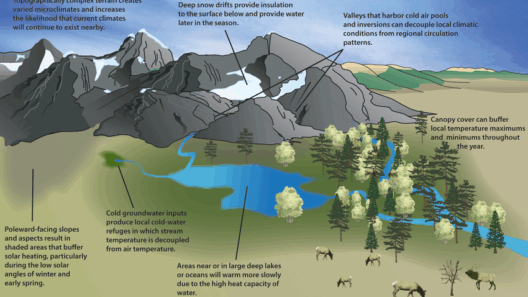

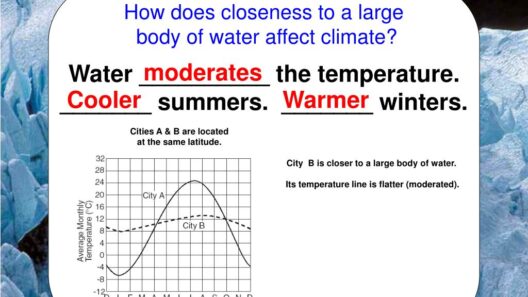

First, let us consider the geographical setting of Japan. Stretching over 3,000 kilometers from north to south, the nation comprises four main islands—Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku—along with numerous smaller islands. This elongated structure plays a critical role in its climatic diversity. When one thinks of Japan’s climate, it is essential to recognize that variations arise not only from latitude but also from elevation and proximity to the sea. With mountains accounting for about 73% of the country’s terrain, we encounter distinct climatic conditions that fluctuate with altitude.

As we transition from the northern reaches of Hokkaido to the temperate climate of Honshu and the subtropical conditions of Kyushu, we observe a fascinating palette of climates. The northernmost island, Hokkaido, is primarily characterized by a humid continental climate. Here, the winters are frigid, often accompanied by heavy snowfall, attracting winter sports enthusiasts from around the globe. Is it any wonder that Hokkaido is home to some of Japan’s most famous ski resorts?

Traveling southward, we encounter the Sea of Japan coast, known for its significant snowfall during winter months. This phenomenon is largely due to the cold Siberian winds meeting the warmer moisture-laden air over the Sea of Japan—a classic interplay of atmospheric conditions that leads to impressive snow accumulations. But what does this tell us about climate resilience in the face of climate change? Will the snow that shapes this region’s identity become a relic of the past?

Honshu, the largest island, presents a fascinating blend of climates. The western side, influenced by the Sea of Japan, sees a higher incidence of precipitation, particularly in the winter months, while the eastern region, including the bustling metropolis of Tokyo, enjoys a humid subtropical climate characterized by hot, humid summers and mild winters. However, the unique geography of Honshu, especially the Japan Alps, introduces local climatic variations, creating microclimates that foster diverse ecosystems, from coniferous forests to alpine meadows.

As we venture further south into Kyushu and Shikoku, one enters the realm of a humid subtropical climate, where the warm Kuroshio Current significantly affects weather patterns. Summers are long, hot, and often humid, while winters remain mild. This climate is also the breeding ground for Japan’s famed cherry blossoms, which have become emblematic of the nation’s cultural identity. How do these delicate yet resilient flowers reflect the intricate relationship between Japan’s climatic zones and its heritage?

The onset of the monsoon season is another critical aspect of Japan’s climatology. Between May and September, the country experiences significant rainfall due to the seasonal shift in wind patterns. The summer monsoon, or the rainy season (tsuyu), can bring torrential downpours, which are both a boon and a bane. While the abundant rain nourishes crops, vital for Japan’s agriculture, it can also lead to disastrous flooding and landslides. How does society balance agricultural benefits against environmental risks?

Interestingly, Japan’s climatic diversity extends beyond typical classifications. The subtropical climate of the Nansei Islands, including Okinawa, further illustrates the juxtaposition of climates. These southern islands experience warm temperatures year-round and a distinct rainy season, making them a popular destination for tropical tourism. The biodiversity here is remarkable, showcasing flora and fauna unlike any found on the main islands. However, as tourism increases, what challenges lie ahead in preserving this delicate ecosystem against the tides of development?

The interplay between these climatic zones is not merely geographical but interwoven with cultural and agricultural practices as well. Farming patterns converge around climate zones—from rice paddies in the fertile lowlands of Honshu to subtropical crops in the south. Each region contributes to the tapestry of Japanese cuisine, which celebrates variations in seasonal ingredients. The essence of local flavors is a direct reflection of the climate, yet, as global warming alters traditional seasons, this connection may face unprecedented challenges.

In sum, Japan’s climate zones are shaped by an amalgamation of geographical features, from its mountainous topography to its oceanic influences. Each region’s climate intricately ties into the lifestyle, agriculture, biodiversity, and culture of its inhabitants. As climate change poses increasing threats to these delicate ecosystems, the resilience of Japan’s landscapes and communities is being tested. Will future generations of Japanese be able to adapt and preserve their unique climatic identity in the face of such challenges? This existential question looms large, challenging all stakeholders—from local communities to policymakers—to contemplate sustainable practices that respect the environment while honoring their rich heritage. The fusion of tradition and modernity in addressing these issues may very well define the future climate narrative of Japan.