The intersection of paper usage and climate change unveils a paradoxical relationship, one that is often overlooked yet critically significant. In an age where digitalization promises to render the paper obsolete, the reality is far more nuanced. As we traverse through the intricacies of this phenomenon, we uncover the surprising link between our documents and global warming, reminding us that the humble sheet of paper can play a pivotal role in our planet’s climate narrative.

Paper, a quintessential product of deforestation, begins its journey as trees in verdant forests. These forests serve as the lungs of our planet, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. The act of harvesting trees for paper production not only displaces this vital ecosystem service but also releases stored carbon back into the atmosphere. The International Paper Association estimates that approximately 40% of the world’s industrial wood harvest is utilized for paper. This staggering statistic unveils the reality that our penchant for written documentation is deeply intertwined with environmental degradation.

However, let us consider the lifecycle of paper. From the tree to the printing press, every stage has implications that extend far beyond mere forest loss. In the production phase, processes such as pulping and bleaching consume energy and water at alarming rates. The tangible paper product emerges only after a cascade of resources have been expended, often leading to the emission of greenhouse gases. The production of a single ton of paper emits roughly 1.7 tons of CO2. Such figures evoke a grim portrait of an industry that balances its cultural significance against its environmental toll.

Nonetheless, the issue does not cease at production. Post-consumer behavior presents another layer of complexity. The disposal of paper primarily occurs through landfill, where its decomposition releases methane, a greenhouse gas with a potency 25 times that of carbon dioxide over a century. Recycling offers a glimmer of hope in this narrative, as repurposing paper can markedly reduce the environmental footprint, recycling 1 ton of paper saves more than 17 trees and prevents the emission of significant amounts of CO2. However, the recycling infrastructure varies globally, and the struggle to establish robust systems leaves many regions vulnerable to the pitfalls of landfill disposal.

Moreover, the paradox continues as the transition to digital documents ostensibly presents a clear solution. The metric may suggest that shifting to a paperless agenda reduces carbon footprints. Yet, this oversimplification dismisses the energy consumption associated with data storage and transmission. Data centers, the backbone of our digital infrastructure, consume an astounding amount of electricity, much of which is derived from fossil fuels. Consequently, the notion of going paperless does not create an automatic net gain for the environment. It underscores the imperative for a holistic approach, examining the entire ecosystem of consumption and deployment rather than isolating paper usage.

In juxtaposition with our digital age, we must ponder the cultural implications of paper. The act of writing on paper fosters a tactile connection, an intimacy that screens struggle to replicate. This intrinsic value of paper cannot be dismissed. Works of art, historical manuscripts, and sensitive documents still demand physicality. This admiration for paper manifests in the irony of “saving trees” campaigns, which inadvertently promote a disconnect from the very process that fuels our ability to interact with the document. Each sheet carries imprinted narratives that shape our thoughts, ideas, and cultures. Yet, our affection for paper can cloud our judgment regarding its ecological impact.

It is vital to emphasize the concept of sustainable paper. Sourcing materials from responsibly managed forests, employing eco-friendly production methods, and investing in recycling technologies encapsulates the trifecta of solutions that can mitigate paper’s adverse effects. Certification programs like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) provide consumers with the ammunition to make informed choices, opting for paper products that prioritize environmental stewardship. The power lies in conscious decision-making, whereby consumers can advocate for brands that honor sustainability over mere profitability.

Education emerges as another pivotal element in addressing paper’s paradox. Greater awareness can lead to behavior modification, embracing practices like double-sided printing, paper-free meetings, and digitizing priority documents. Schools, corporations, and institutions must cultivate a culture of ecological mindfulness, orienting understanding away from mere usage to an appreciation of resources at large. This ethos of responsibility extends beyond paper; it encompasses the broader scope of consumption in the face of climate change.

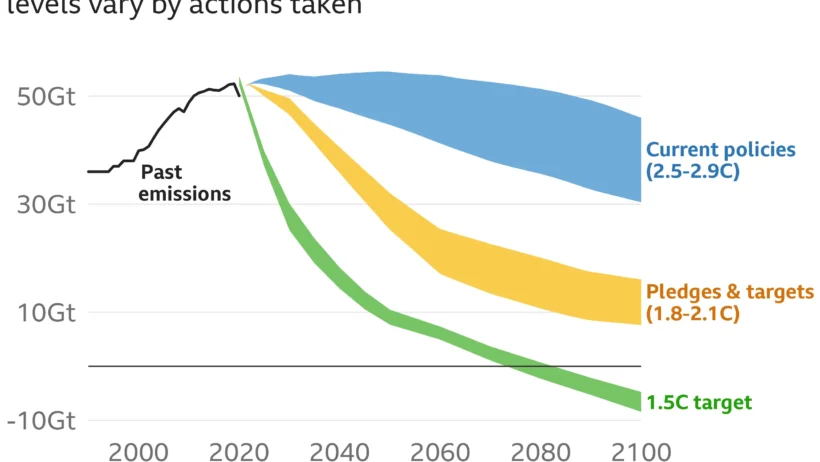

As we thoroughly dissect the complexities of paper’s role in climate change, the narrative transforms from one of villainy to one of redemption. The onus lies with consumers, industries, and policymakers alike to create sustainable practices that harness the benefits of paper without succumbing to its ecological costs. The invitation to reconcile our needs for documentation with environmental integrity is a clarion call for collective action.

In conclusion, the figurative weight of our documents holds more than academic or corporate significance; it carries the aspirations and responsibilities of our generation. The paradox of paper is a microcosm of the broader struggles within our relationship to the environment. As we transition toward a more sustainable future, embracing an ethos that honors both our linguistic history and environmental fidelity is essential. The journey ahead is daunting, yet, through informed choices and a dedication to sustainability, we can mitigate the paradox and champion a balanced approach to our documentation needs. The message resonates: every page matters. Choose wisely.