The New England Colonies, encompassing present-day Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, are characterized by their distinct climate and geography. These factors had profound impacts on the social, economic, and political landscapes during the colonial period. But have you ever wondered how the frigid winters influenced political decisions and societal structures? It poses a perplexing challenge: did the climatic adversities catalyze a level of governance and resilience that shaped the very fabric of these early colonial societies?

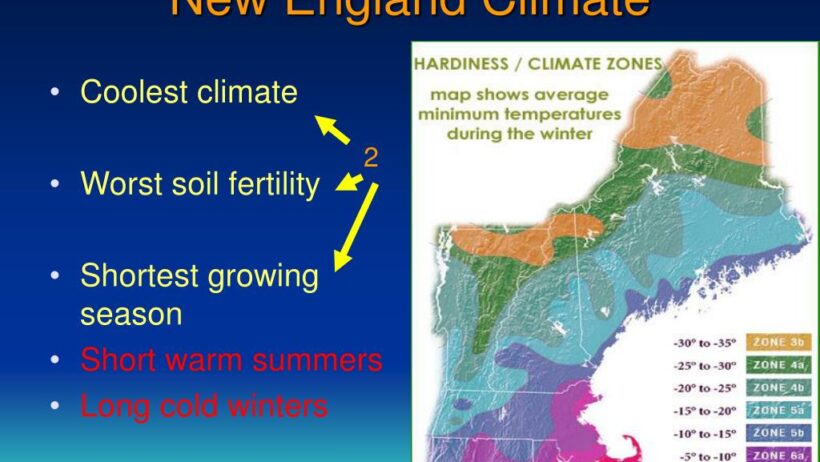

The climate in New England can broadly be described as humid continental, with significant seasonal variations. Winters are notoriously harsh, featuring heavy snowfall and frigid temperatures that can plummet well below freezing. Conversely, summers, while milder, exhibit a considerable amount of humidity and precipitation, creating an environment that supports both agriculture and forestry. This dichotomy presents an argument that the very extremes of New England’s weather influenced the colonies’ development.

During the early colonial era, European settlers faced numerous obstacles as they endeavored to establish their communities. The abysmal winters prompted immediate adaptive measures. One effect of these harsh winters was a reliance on communal practices. In the face of adversity, settlers banded together for mutual survival. Shared resources and collaborative efforts became prominent as families struggled against the relentless cold. Such cooperation fostered strong communal ties, leading to the establishment of rudimentary forms of governance.

As winter approached, the urgency to prepare for the upcoming months intensified. What began as a survival strategy morphed into a political necessity. The challenge of facing a common enemy—the winter itself—encouraged a collective societal identity. In towns like Plymouth and Salem, town meetings evolved into democratic forums where decisions regarding resource allocation and development were made with the input of all eligible members. This early form of participatory governance in New England colonies can be directly linked to the pragmatism demanded by their environmental context.

Yet, the intertwining of climate and politics in New England did not yield a harmonious relationship. Ironically, the same climate that promoted cooperation also fostered tensions. As agricultural production fluctuated with the seasons, economic stability often wavered. For instance, crops facing significant stress during cooler, wetter years could lead to shortages, inciting competition among settlers and, in some cases, conflict. This points to a duality wherein adversities induced collaboration while simultaneously stirring political tensions that led to disputes over land, resources, and labor.

The political ramifications of this climate-induced competition were significant. The struggle for territory and economic resources ignited a complex web of political alliances and rivalries among the settlers. Settlement patterns were influenced by climatic conditions, with fertile river valleys becoming focal points for some of the most contentious land disputes. The challenging winters necessitated that settlers occupy and defend these prime plots of land. Consequently, land ownership became a pivotal aspect of political power dynamics in New England, often dictated by one’s ability to endure the relentless climate.

Moreover, the environmental challenges faced by these early colonists culminated in a robust discourse around governance and rights. As inhabitants grappled with the exigencies of their climate, they became increasingly vocal about their grievances against colonial powers. The harsh winters were emblematic not only of nature’s cruelty but also of the perceived tyranny practiced by colonial authorities in affluent nations across the Atlantic. This growing sense of injustice would eventually culminate in broader movements of resistance, exemplified in events leading up to the American Revolution.

Furthermore, the economic systems in the New England Colonies were similarly tied to climatic conditions. With agriculture heavily reliant on seasonal cycles, towns became adept at diversifying their economies to mitigate risks. Coastal regions took advantage of maritime resources, establishing fishing and trade networks that became critical in buoying local economies during the more challenging months. The climate’s harshness fostered a spirit of entrepreneurship; settlers were compelled to innovate and adapt, whether through the barter of goods or the establishment of early industries.

Indeed, these environmental influences instigated not only local economic adaptations but also broader political ramifications. As settlers interacted with indigenous populations, the demand for land expanded, leading to complex relations fraught with mistrust and conflict. The climate played an instrumental role in these encounters; for instance, poor harvests could lead to desperation and hostility, further complicating the trans-cultural dynamics in New England.

In retrospect, the relationship between climate and politics in the New England Colonies presents a compelling paradox. The very adversities that tested the mettle of these early settlers also sowed the seeds of a burgeoning political discourse centered on rights, governance, and economic autonomy. While winter’s chill can stifle growth, it equally ignites the sparks of innovation and resistance. How might history have unfolded differently had these colonies been blessed with milder winters? Such hypothetical musings underscore the reality that the climate is not merely a backdrop to human affairs but a formidable force that influences trajectories in governance and social interaction.

In conclusion, the intertwining of the harsh climate and political development in the New England Colonies presents an intricate tapestry of human resilience. Engaging with the environment’s challenges prompted settlers to develop systems of governance and cultivate communal bonds, while simultaneously giving rise to tensions that shaped political landscapes. The duality of harsh winters and hot politics remains a significant chapter not just in colonial history but in understanding the broader relationship between environment and society.