The COVID-19 pandemic has undeniably altered the fabric of global society. Yet, embedded within this unprecedented crisis lies a harrowing juxtaposition: the Coronavirus Climate Paradox. The world witnessed dramatic reductions in carbon emissions during the lockdowns initiated to curb the virus’s spread. This phenomenon raises a salient question: can a global downturn in activity provide insight into sustainable practices that might mitigate humanity’s long-term impact on climate change, or is it merely a fleeting anomaly?

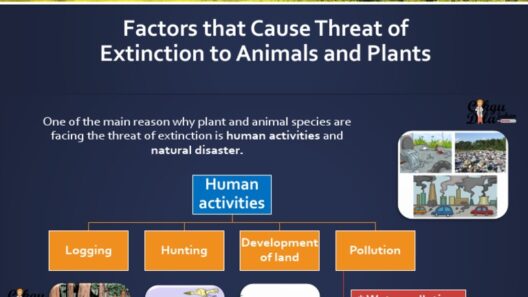

To delve into this paradox, we must first understand the mechanics of greenhouse gas emissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has consistently warned that exceeding carbon dioxide levels of 350 parts per million could amplify global warming effects, leading to catastrophic climate destabilization. The pandemic inadvertently provides a poignant case study on how human activity directly correlates with emissions output.

During the early months of 2020, as cities around the globe locked down, air quality phenomena were observed. For example, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels decreased significantly in urban centers known for pollution, such as Los Angeles and New Delhi. This sudden dip in emissions presented an unprecedented opportunity: the chance to witness the fleeting effects of reduced industrial activity and transportation on atmospheric composition. While positive, these changes are not entirely encouraging, as they stemmed from a crisis rather than conscious environmental efforts.

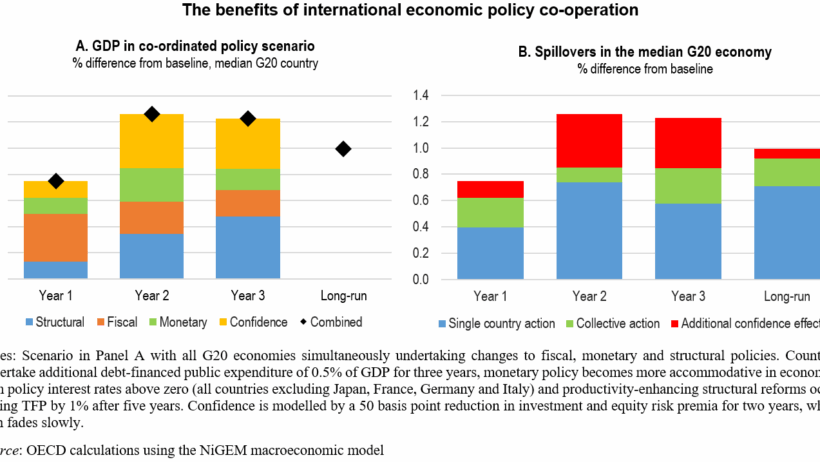

The paradox grows more complex when examining the socio-economic ramifications of the pandemic. While emission levels plummeted, so too did employment rates and economic stability, particularly in sectors reliant on fossil fuels. Governments around the world initiated stimulus packages to revitalize their economies. The challenge lurked within these economic policies: would recovery efforts prioritize ecological sustainability or resume the pre-pandemic trajectory of fossil fuel dependency? As nations grappled with balancing economic recovery and environmental commitments, the question of how to recover without re-imbibing previous harmful practices emerged as a critical concern.

Furthermore, a longitudinal analysis reveals the notion of “pandemic recovery” intertwined with climate repercussions. As restrictions eased, a notable resurgence in carbon emissions rapidly ensued, highlighting the phenomenon aptly dubbed the “rebound effect.” Analysts projected that as economies recovered, emissions could surpass even the levels observed before the pandemic. This cycle poses a fundamental challenge: can societies learn from the transient glimpse of cleaner air and skies to instigate long-term behavioral changes?

Governments and organizations must recognize the potential inherent in this challenge. Now is the time for transformative policies that emphasize green technologies, sustainable urban planning, and environmental education. For instance, the adoption of telecommuting practices, once a necessity, could transition into a long-lasting norm, reducing commutes that heavily contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, industries could divert investments towards renewable energy sources rather than returning to the predilections of fossil fuel reliance.

Yet, the fundamental dilemma lies in capitalizing on the momentum garnered during this crisis. Activists and policymakers face an uphill battle against ingrained ideologies that prioritize immediate economic gain over sustainable practices. The paradox reveals the contradiction of a society that expresses urgency towards climate action while often defaulting to status quo approaches in times of recovery.

Emerging from the pandemic necessitates a cultural shift towards conscientious consumerism and environmental stewardship. Individuals have a role to play as well; the pandemic showcased the power of collective action, wherein small lifestyle changes multiplied across populations can collectively reduce emissions. For instance, a notable rise in local food purchasing and reduced plastic usage were observed during lockdowns, signaling a shift in consumer preferences that could catalyze supporting local economies while fostering environmental resilience.

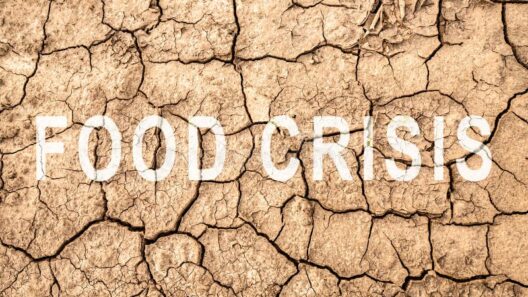

However, amidst the hopeful narrative, it is essential to underscore the systemic barriers impeding climate progress. For many, the average focus remains on immediate survival, making climate activism a luxury rather than a priority. The challenge then becomes one of equity; how can we ensure that marginalized communities, often disproportionately affected by both the pandemic and climate change, can participate and benefit from the green recovery? Legislative frameworks must prioritize inclusivity to engender a resilient future for all.

The economic recovery phase, compared to historical precedents post-crisis, reveals a stark reality: without robust advocacy, the inertia towards fossil-fueled growth can easily re-establish itself. Thus, various stakeholders, from grassroots organizations to powerful governments, must work cohesively to redesign societal frameworks around sustainability. A critical question arises: Are we willing to learn from this experience and pivot towards a more resilient, sustainable future, or will we revert to our previous patterns as the proverbial comfort of normalcy beckons?

As the world emerges from this crisis, the opportunity to bridge the gap between post-pandemic recovery and climate action looms large. The paradox is indeed troubling—one that symbolizes a hairstreak moment for the environment, capable of propelling us towards greener choices or regressing us into destructive patterns. The way forward is tethered to our capacity for self-reflection and collective action; unless pursued with intent and commitment, the extraordinary clarity revealed during the pandemic may once again fade into obscurity.

Ultimately, the Coronavirus Climate Paradox invites society to confront some uncomfortable truths about consumption, responsibility, and governance. Tracing back to the playful yet challenging question, for how long can we sustain the gains of reduced emissions, or will we allow the allure of economic revival to drown our resolve for lasting change?