The Kyoto Protocol, established in 1997, represented a watershed moment in international environmental diplomacy aimed at curbing the escalating threat of global warming. It was, in essence, a promise—a commitment made by nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to mitigate climate change. Yet, as we stand on the precipice of unprecedented climatic shifts, one must ponder: Can the Kyoto Protocol serve as a viable blueprint to halt the relentless march of global warming? Or does it merely mask the deeper complexities of addressing this existential threat?

To begin dissecting this pivotal agreement, it is essential to grasp its foundational structure. The Kyoto Protocol mandated that industrialized nations—those historically responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions—commit to reducing these emissions by an average of 5.2% below 1990 levels over a commitment period running from 2008 to 2012. The protocol was groundbreaking in its recognition of the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” which acknowledged that while all countries are responsible for combating climate change, not all share equal blame or capacity to act.

However, the implementation of the protocol encountered significant obstacles. The United States, which at the time was the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, famously declined to ratify the agreement. This absence raised a daunting question: How can a collective international effort succeed when key players refuse to participate? This conundrum was exacerbated by the lack of binding commitments for developing nations. Nations such as China and India were permitted to increase their emissions under the agreement, relying instead on technology transfer and financial support from the developed world. Critics argue that this lack of comprehensive accountability undermined the protocol’s goals, creating an atmosphere of ambiguity.

As nations embarked on the journey to implement the Kyoto Protocol, the effectiveness of its regulatory mechanisms came into question. The tradeable emission permits system, which aimed to provide economic incentives for countries to reduce emissions, introduced a new dimension to climate diplomacy. Yet, such market-based approaches can be likened to navigating a ship through a dense fog; without clear visibility on effectiveness, countries may exploit loopholes or engage in “carbon credit trading” without genuinely reducing emissions. Can a system that ostensibly assigns economic value to pollution truly inspire substantive action against climate change?

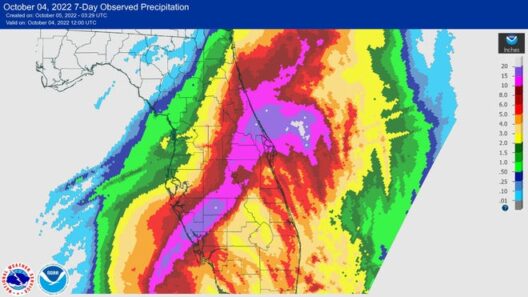

Moreover, the Kyoto Protocol faced an unforgiving reality: the continually escalating symptoms of global warming. Natural disasters, rising sea levels, and shifting weather patterns have caused widespread devastation. The perseverance of these phenomena amidst international agreements highlights a pertinent question: Is the Kyoto Protocol a pragmatic framework or a symbolic gesture? The gap between the stated goals and actual outcomes suggests that lofty ideals can sometimes be a hindrance rather than a help in fostering genuine progress.

In reflection, the lessons garnered from the Kyoto Protocol can illuminate the path forward. While it may not have produced the wide-scale transformations that many anticipated, it undeniably spurred critical discourse about climate responsibilities. The intergovernmental panel established under the protocol fostered a plethora of scientific research into climate change, thus catalyzing continued conversations about viable strategies to combat this pressing crisis.

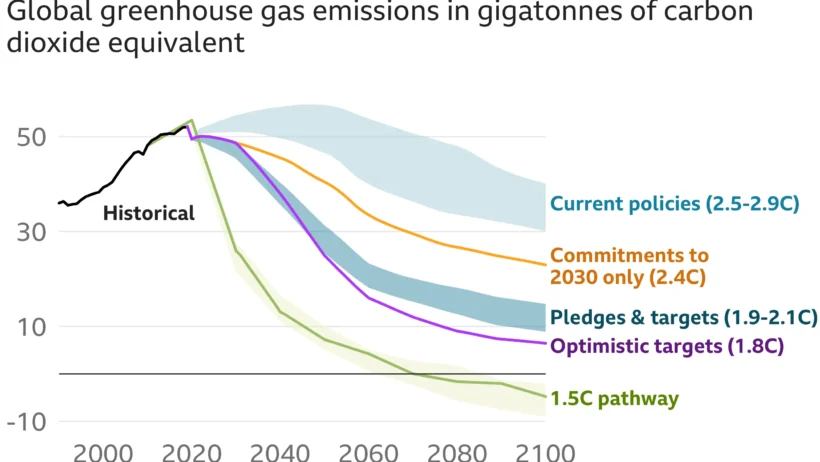

Nonetheless, emerging from the shadows of Kyoto are contemporary agreements such as the Paris Agreement, which has initiated a renewed dialogue on reducing global emissions. Unlike its predecessor, the Paris Agreement emphasizes voluntary, nationally determined contributions (NDCs), allowing countries to tailor their commitments based on their unique socio-economic contexts. While this approach might offer flexibility, it raises a crucial concern: Could this leniency dilute the urgency with which rapid action must be undertaken? Are we potentially erecting a framework that endorses procrastination?

The Kyoto Protocol’s legacy remains a dual-edged sword. It stands as an emblem of international cooperation while simultaneously invoking the specter of insufficient action against the escalating climate crisis. The protocol sparked a paradigm shift in how we perceive our responsibilities toward the earth’s climate; however, the efficacy of its mechanisms has necessitated re-evaluation.

As the global community grapples with burgeoning climate challenges, the tension between aspirations and realities comes to the forefront. The chronicles of climate agreements underscore a pivotal realization: isolated efforts yield limited results. A harmonious alignment between scientific imperatives and political will is indispensable for transcending mere symbolic gestures toward decisive action. Can the spirit of the Kyoto Protocol, infused with its lessons and critiques, serve as the catalyst for a more unified global response?

Ultimately, while the Kyoto Protocol may not have completely halted the advance of global warming, it is undeniably a chapter in a larger narrative of environmental stewardship. Its intentions were noble; its challenges profound. As new frameworks emerge, the conceptual scaffolding established by Kyoto can guide future international efforts, urging nations to move beyond fragmented initiatives, towards a cohesive strategy that demands accountability. After all, in the dire pursuit against climate change, the time to act is now, and the lessons learned must not be in vain. The stakes have never been higher, and the imperative for action has never been clearer. Can humanity rise to meet this monumental challenge?