The ozone hole and global warming are often juxtaposed in discussions surrounding climate change, leading to numerous misconceptions and confusions. This intricate relationship requires clarification. By unraveling the complexities of both phenomena, we can better understand their connections and implications. While they stem from different causes, their impacts intertwine, engendering varying environmental challenges.

To begin, it is crucial to differentiate between the ozone layer and the greenhouse effect. The ozone layer, predominantly located in the stratosphere, serves as a protective shield that absorbs the majority of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. Conversely, the greenhouse effect is a natural process wherein certain gases trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, which is essential for maintaining a stable climate. However, when excessive greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, accumulate due to human activities, they disrupt this balance and contribute to global warming.

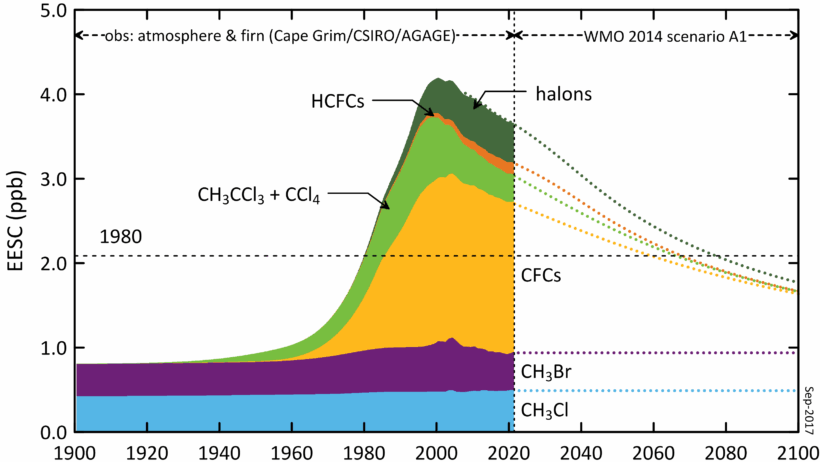

The infamous ozone hole, first identified in the late 20th century, is primarily attributed to human-made chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). These substances, once prevalent in aerosol propellants, refrigerants, and foam-blowing agents, cause the degradation of ozone molecules. This destruction is most pronounced over Antarctica during the Southern Hemisphere’s spring, resulting in a significant thinning of the ozone layer. The repercussions of this phenomenon are severe; increased ultraviolet radiation reaching the Earth’s surface can lead to higher incidences of skin cancer, cataracts, and adverse effects on terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

On the surface, one might conclude that the ozone hole and global warming are interlinked due to their shared roots in human activity and environmental degradation. However, upon deeper examination, it becomes evident that they are distinct yet intersecting issues. While they are both exacerbated by anthropogenic influences, the mechanisms underlying their development and consequences diverge. CFCs are not significant contributors to greenhouse gas concentrations, and thus, their onset of the ozone depletion does not directly induce global warming. Rather, the two phenomena exist in a complex relationship marked by indirect connections.

The Montreal Protocol, an international treaty established in 1987, was aimed at phasing out the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances, particularly CFCs. This monumental agreement has yielded significant successes. It is often heralded as a triumph in global environmental governance, leading to a gradual recovery of ozone levels. Nonetheless, while the ozone layer’s resurgence provides reason for optimism, it does not negate the persistent threats of climate change.

An essential question arises: Are the fixes for the ozone layer compatible with strategies aimed at mitigating global warming? In some cases, yes. The strategies adopted to reduce CFCs contribute to climate stabilization. Many substitutes for ozone-depleting substances are less potent greenhouse gases and employing these alternatives can provide multifaceted benefits. Thus, the continued observance and enforcement of protocols designed to eradicate CFCs might assist in tempering the overall pace of global warming.

However, the notion that addressing one issue will inherently resolve the other is a fallacy that must be dispelled. A shallow perspective often leads to the assumption that a fix for ozone depletion could serve as a panacea for climate change. This is a dangerous misinterpretation. The culprits of global warming, such as carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion, demand a unique suite of solutions. While there are synergies in addressing both issues, it must be recognized that they are separate challenges requiring dedicated strategies and vision.

Moreover, a fundamental inquiry into the long-term ramifications of the ozone hole on global warming actions is warranted. Some studies suggest that ozone depletion might actually exacerbate climate change through atmospheric interactions. The loss of ozone can alter weather patterns, potentially destabilizing climatic systems and further complicating the battle against global warming. This intersection, where atmospheric science meets climatology, demands rigorous investigation, and underscores the necessity for integrated research approaches.

Additionally, the public narrative surrounding these topics could benefit from a paradigm shift. Presenting the ozone hole and climate change as disparate issues restricts understanding. Instead, framing them within the broader context of environmental health serves to enrich discussions. This perspective encourages individuals to view their actions not merely as local or isolated incidents but as integral parts of a global ecosystem—one in which every effort counts.

The implications of ignoring this relationship are profound. As global citizens and stewards of our planet, a failure to comprehend the connections between the ozone layer and climate change can lead to ineffective policy decisions. It bears emphasizing that both crises necessitate urgent and enduring action. By promoting awareness and generating dialogue, we can galvanize collective efforts towards comprehensive solutions that honor our commitment to safeguarding the Earth’s atmosphere.

In conclusion, while the ozone hole and global warming arise from separate yet interconnected roots, understanding their nuances can lead to more informed choices. Rather than viewing them in isolation, a comprehensive approach validates the interdependencies of ecological systems. The restoration of the ozone layer, coupled with earnest endeavors to combat climate change, holds the promise of a sustainable future. This dual focus not only cultivates curiosity but also empowers individuals to engage in the critical discourse surrounding environmental stewardship, ultimately leading to a healthier planet for generations to come.