The production paradox explores the intricate relationship between mass manufacturing and climate change. It illuminates the ways in which industrialization, while instrumental in economic growth, concurrently exacerbates environmental degradation. The foundation of this paradox lies in the undeniable reliance of modern economies on mass production to fulfill consumer demands. However, this reliance propels a cycle of depletion, pollution, and ecological imbalance.

At the core of mass manufacturing is the imperative to produce goods at an unprecedented scale. The advent of industrialization in the 18th and 19th centuries marked a significant shift in production methodologies. Factories sprouted up, adopting mechanization that enabled the rapid production of commodities. This efficiency, touted as a hallmark of progress, set the stage for an insatiable consumption model. Today, the world produces more in a day than it ever did in a month just a century ago.

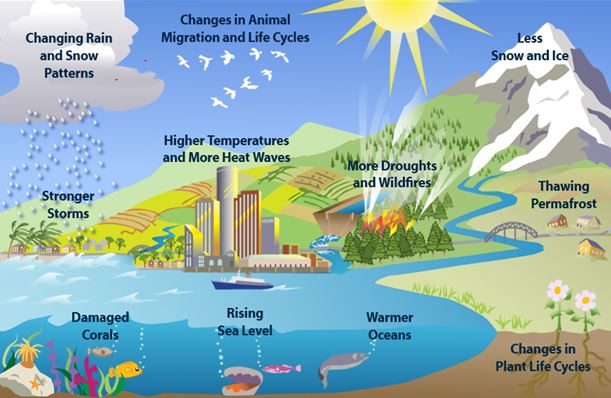

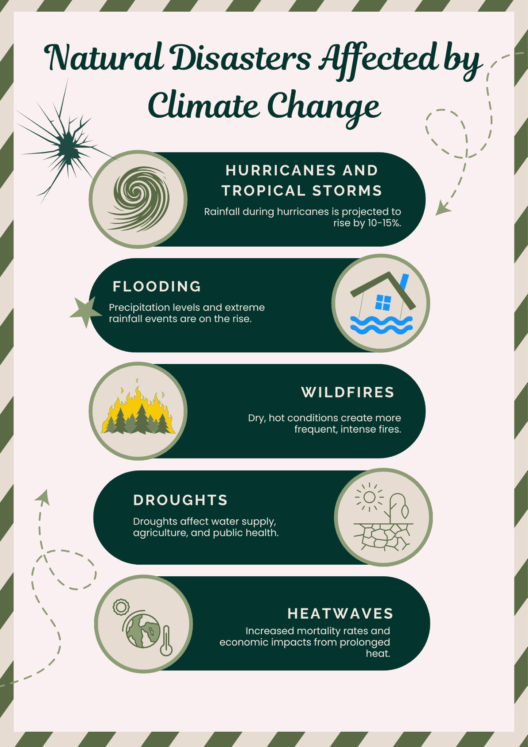

Despite the apparent advantages of increased production, the environmental ramifications are troubling. The production processes often hinge on fossil fuels, which are notorious for their contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. Manufacturing facilities emit significant amounts of carbon dioxide and other pollutants, which accumulate in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. In essence, the very processes that stimulate economic advancement simultaneously jeopardize environmental stability.

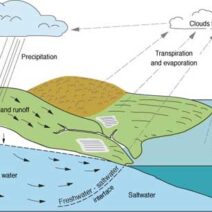

The paradox deepens when one considers the lifecycle of manufactured goods. From raw material extraction to product disposal, each phase of production has an ecological footprint. Extracting resources requires land, energy, and water—crucial resources that are often depleted faster than they can be replenished. Deforestation, water scarcity, and loss of biodiversity are common byproducts of this incessant demand for raw materials. Moreover, the transportation of these materials, whether via land, air, or sea, further exacerbates carbon emissions, perpetuating the cycle of harm.

Additionally, the concept of planned obsolescence plays a pivotal role in this narrative. Manufacturers design products with a limited useful lifespan, compelling consumers to replace items more frequently. This artificial scarcity not only drives sales but also intensifies the volume of waste generated. Landfills across the globe are overflowing, and hazardous waste often leaches into soil and waterways, endangering public health and ecosystems alike.

Furthermore, the phenomenon of consumerism cannot be understated. The modern economy thrives on a culture that equates consumption with status and success. Advertising and marketing campaigns perpetuate the notion that new goods equate to happiness, steering consumers into an endless cycle of acquisition. This consumerist mentality sustains demand for mass production, further entrenching the environmental costs associated with manufacturing processes.

Globalization has amplified this production paradox. As companies seek to capitalize on lower labor costs, manufacturing has shifted to developing countries. This relocation often results in lax environmental regulations, where companies exploit natural resources without regard for sustainability. The resulting export of pollution from wealthier nations to countries with fewer environmental protections paints a troubling global landscape. As goods are produced in one part of the world and consumed in another, the environmental impact becomes obscured, creating a false sense of security regarding the direct connection between production and ecological health.

In an effort to combat the negative consequences of mass manufacturing, various sustainability measures have emerged. The adoption of eco-friendly production techniques aims to minimize waste and reduce emissions. Innovations such as circular economy models propose the idea of reusing materials and reducing dependence on virgin resources. Companies are increasingly embracing sustainable practices, seeking to position themselves as responsible stewards of the environment. However, the effectiveness of these initiatives is often limited by the underlying economic motivations that prioritize profit over planet.

Technological advancements also offer potential solutions. The rise of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower presents an opportunity to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Incorporating green technologies into manufacturing processes can significantly lower carbon footprints. However, investing in such transformations is often hindered by the high initial costs and resistance to change within established industries.

The production paradox serves as a compelling reminder of the dual nature of mass manufacturing. While it fulfills immediate economic needs, it simultaneously poses a substantial threat to global ecosystems. The fragility of our environment necessitates a reevaluation of how societies conceptualize production and consumption. Moving forward, fostering a culture of sustainability will be imperative.

Ultimately, addressing the production paradox requires collective action from individuals, corporations, and governments. Consumers must cultivate an awareness of their purchasing habits, opting for products that are sustainably sourced and ethically produced. In parallel, policymakers must enforce stricter regulations that diminish the environmental impact of manufacturing processes. By holding industries accountable and incentivizing sustainable practices, society can cultivate an equilibrium between economic growth and environmental preservation.

In conclusion, the production paradox encapsulates the complex interplay between mass manufacturing and climate change. It highlights the essential need for a paradigm shift in how we produce and consume goods, advocating for practices that support a sustainable future. The pressing challenges posed by climate change demand that the world reimagine its relationship with production, ensuring that economic advancement does not come at the expense of ecological integrity.