Climate controls are the intricate threads that weave the tapestry of our planet’s climate. They are the hidden architects of weather patterns that govern everything from the gentle breezes to torrential downpours. By understanding these controls, we can better appreciate how they shape our ecosystems, influence human activity, and ultimately impact the sustainability of life on Earth.

At the heart of climate controls are both natural and anthropogenic factors. Natural climate controls are primarily driven by geographical features, solar radiation, and atmospheric dynamics. These elements create a complex ballet that dictates regional climates across the globe.

Geographical Features

The planet’s topography is akin to a grand symphony, with mountains serving as the formidable percussion and valleys as the melodious strings. Mountain ranges play a crucial role in shaping climate by intercepting moisture-laden winds, leading to phenomena such as rain shadows. When moist air ascends over a mountain, it cools and condenses, resulting in precipitation on the windward side while leaving the leeward side parched and arid. This occurrence is vividly illustrated in locations such as the Himalayas, where lush forests flourish on one side, while the other end transitions into arid desert landscapes.

Latitude and Solar Radiation

Latitude acts as the compass directing the intensity and distribution of solar radiation. The Earth’s curvature means that sunlight strikes the equatorial regions more directly than it does at the poles. This uneven heating creates tropic zones characterized by high temperatures and abundant rainfall, while polar regions experience extreme cold and minimal precipitation. The implications of latitude extend beyond mere temperature variations; they mold ecosystems and dictate the types of flora and fauna that can thrive in each region.

Atmospheric Circulation

The movement of air masses forms a dynamic system reminiscent of the ocean currents that traverse the seas. Atmospheric circulation is driven by the differential heating of the Earth’s surface and is responsible for the prevailing winds that whisk across continents. The Coriolis effect, resultant from the Earth’s rotation, further complicates this system, deflecting winds and creating the jet stream—a high-altitude, fast-flowing air current that significantly affects weather patterns. The interplay of these atmospheric currents results in phenomena such as trade winds and westerlies, which collectively contribute to the distribution of heat and precipitation.

Ocean Currents

Ocean currents serve as Earth’s circulatory system, transporting heat across vast distances and influencing coastal climates. Warm currents, like the Gulf Stream, elevate temperatures in adjacent areas, contributing to milder winters in otherwise colder regions. Conversely, cold currents can create chillier conditions, exemplified by the California Current, which cools the western coast of North America. These interactions between the ocean and atmosphere create microclimates that can lead to significant climatic variances even within short distances.

Anthropogenic Influences

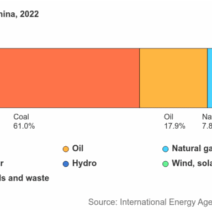

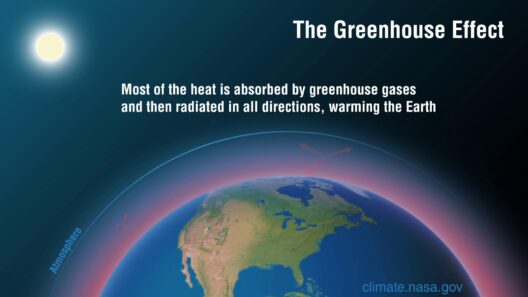

Human activity has gradually woven itself into the fabric of climate control, creating dissonance with natural systems. Industrialization, urbanization, and deforestation have introduced unprecedented levels of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. These gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, trap heat and lead to global warming. The implications of anthropogenic climate controls are profound, altering weather patterns, melting glaciers, and driving sea-level rise.

The introduction of urban heat islands exemplifies how human infrastructure can modify local climates. Cities, with their immense concentrations of concrete and steel, absorb and retain heat more effectively than rural areas, thus influencing local weather conditions. The increased energy consumption in urban environments corresponds with heightened carbon emissions, further exacerbating climate change.

Feedback Mechanisms

Feedback mechanisms either amplify or dampen the effects of climate controls. Positive feedback loops, such as those seen in Arctic ice melt, serve as stark warnings. As the planet warms, ice caps begin to melt, reducing the Earth’s albedo—the reflective quality of surfaces—causing more solar energy to be absorbed rather than reflected. This additional absorption accelerates warming, creating an unrelenting cycle. In contrast, negative feedback mechanisms, like increased cloud cover, could theoretically work to mitigate warming by reflecting solar radiation back into space. However, the complexity of these interactions creates uncertainty in predicting the full scope of climate responses.

Climate Zones

The culmination of all these factors produces distinct climate zones around the globe, each with its own unique characteristics. Tropical, arid, temperate, polar, and Mediterranean climates represent a spectrum that influences ecosystems, agriculture, and habitability. For instance, the tropical rainforest thrives in regions with abundant rainfall and consistent warmth, supporting a remarkable diversity of life. In contrast, arid zones, like deserts, present harsh challenges for survival, fostering adaptations that are marvels of evolution.

Conclusion

Understanding the climate controls that shape our planet is vital for fostering a deeper connection to the environment. As we navigate the challenges posed by climate change, we must recognize the intricate balance of natural and human influences that govern our climate systems. This knowledge empowers us to take meaningful action toward sustainability. The orchestra of climate controls continues to play, and it is our responsibility to ensure that its music remains harmonious for future generations.