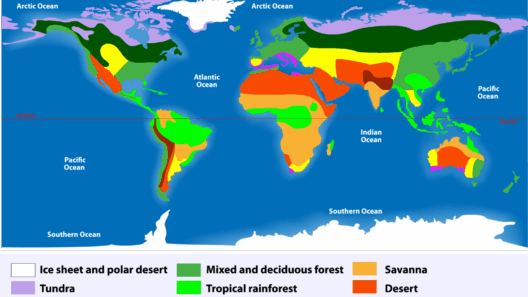

The tundra, often characterized as Earth’s frozen frontier, represents one of the most inhospitable climates on the planet. It is a biome marked by sub-zero temperatures, permafrost, and a unique array of flora and fauna that have adapted to the extreme conditions. Understanding the climate of the tundra and the life it supports provides insight into not only this specific ecosystem but also the broader implications of climate change on fragile environments.

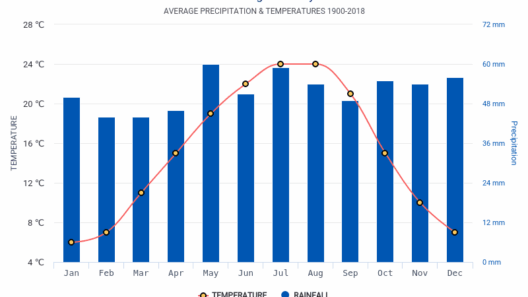

The tundra is predominantly located in the Arctic regions of North America, Europe, and Asia, as well as in certain alpine areas of the world. Its climate is classified as polar, with average temperatures that rarely rise above freezing for most of the year. Winter temperatures often plummet to -30 degrees Celsius (-22 degrees Fahrenheit) or lower, while summer temperatures may reach a maximum of 10 to 15 degrees Celsius (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) for a brief period. This temperature variation, while seemingly slight, plays a critical role in the ecosystem’s functions and the organisms that inhabit it.

Precipitation in the tundra is minimal, typically ranging from 15 to 25 centimeters (6 to 10 inches) annually. Most of this moisture comes in the form of snow, which blankets the ground in winter and contributes to the region’s unique hydrology in spring. The short growing season, lasting only a few months, necessitates that plant life be hardy and efficient. During the summer, the top layer of soil thaws, allowing for a burst of vegetation. This brief period of warmth transforms the tundra into a vibrant tapestry of life, as various species vie for limited resources.

During the extremely long winters, entire ecosystems enter a state of dormancy. The frozen ground, known as permafrost, inhibits root development and limits the types of vegetation that can thrive. However, despite these challenges, life persists. The tundra is home to a variety of plant species, including lichens, mosses, and low shrubs, all of which have adapted specific survival strategies. For instance, many tundra plants are perennial, which allows them to conserve energy throughout the harsh months and flourish rapidly during the warmer summer periods.

Animal life in the tundra has also evolved to withstand the severe climate. Species such as the Arctic fox, caribou, and snow owl exhibit remarkable adaptations to their frigid environment. The Arctic fox, with its thick double coat and keen sense of hearing, can hunt for rodents beneath the snow. Caribou, meanwhile, are known for their extensive migrations and impressive adaptations to traverse snowy landscapes in search of food. These animals often rely on the vegetation that emerges during the summer months, creating intricate food webs that support various other organisms, including migratory birds and ground-nesting species.

Despite the harshness of the tundra climate, interactions among species foster a rich tapestry of life. The relationships are symbiotic; for instance, various bird species rely on the insects that thrive during the brief summer to provide essential protein for their young. The interdependence observed in the tundra’s ecosystems underscores the interconnectedness of life and the vulnerability of these relationships to climate changes.

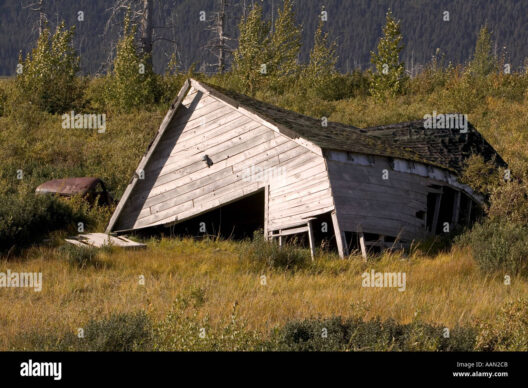

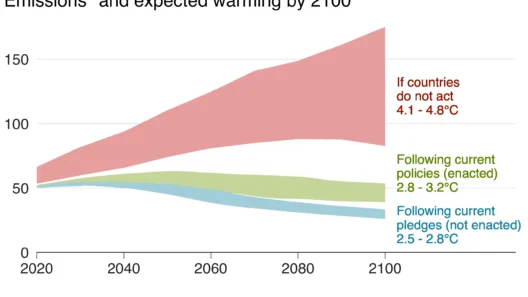

As climate change accelerates, the tundra is experiencing significant transformations. The warming temperatures are causing permafrost to thaw, which releases greenhouse gases like methane into the atmosphere. This release exacerbates the climate crisis, creating a feedback loop that intensifies global warming. Moreover, the changing climate disrupts traditional migratory patterns and breeding cycles of tundra species. For instance, migratory birds may find that food sources are less available during their nesting season due to the timing mismatch caused by the rapid rise in temperatures.

Additionally, invasive species are a growing concern. As the tundra warms, non-native species are increasingly capable of establishing themselves in these formerly inhospitable regions. This can lead to competition for resources, further straining the native populations that have adapted over millennia to the unique tundra conditions. Such changes highlight the fragility of the tundra ecosystem and its susceptibility to external pressures from climate change and human activities.

This ecological vulnerability serves as a rallying point for environmental activism and scientific research. Understanding the intricacies of the tundra biome is essential, not only for conserving its unique biodiversity but also for mitigating the broader implications of global climate change. Educational programs and awareness campaigns play a crucial role in informing the public about the significance of tundra ecosystems and their rapidly changing realities.

In conclusion, the tundra represents a remarkable yet delicate ecosystem that embodies the extremes of climate on Earth. The interplay of climate, vegetation, and animal life showcases both resilience and vulnerability in the face of a changing world. As we confront the realities of climate change, the tundra stands as a stark reminder of what is at stake and an urgent call to action to safeguard these vital ecosystems for future generations.