The climate of the savanna is a complex interplay of wet and dry seasons, characterized by distinct patterns that differentiate this unique biome from other ecological zones. Savannas are primarily found in regions reminiscent of Africa, Australia, and South America, where they straddle the equatorial belt. This climactic dichotomy is vital to understanding the species that thrive within this ecosystem, along with their survival strategies.

First and foremost, savannas are marked by their temperate climate, which oscillates between periods of drought and copious rainfall. Typically, savanna climates feature a distinct wet season, which can last from several weeks to several months, followed by an extended dry season that can be unrelenting. The annual precipitation in savanna regions usually ranges from 20 to 50 inches, primarily concentrated in the wet season. The lush grasses and occasional trees that define the savanna biome flourish during this time, providing a rich tapestry of life.

The vast expanse of savanna grasslands is often classified into two main types: tropical savannas and temperate savannas. Tropical savannas, found predominantly near the equator, experience relatively uniform temperatures year-round, often averaging between 68°F and 86°F. Conversely, temperate savannas, located further from the equator, exhibit a broader range of temperatures. These variations can reach extremes of frost during winter months, impacting the flora and fauna that reside there.

Temperature fluctuations play a fundamental role in defining the climate of the savanna. During the dry season, temperatures can soar—often exceeding 100°F—creating an inhospitable environment for many species. Savanna inhabitants have adapted to these arid conditions, exhibiting behaviors that mitigate heat stress. Larger mammals, such as elephants and wildebeests, are known to be more active during the cooler parts of the day, seeking shade during the unforgiving midday sun.

Vegetation within the savanna biome is typically adapted to survive prolonged dry spells. The predominant flora includes grasses that have deep root systems capable of tapping into underground moisture. Grasses in savannas regularly grow to heights of three to ten feet, forming vast carpets of green, punctuated by clusters of acacia and baobab trees. This sparse tree cover is not merely decorative; these trees often bear adaptations that allow them to withstand drought, such as drought-resistant bark or foliage that minimizes water loss.

The interdependence of flora and fauna in the savanna is also noteworthy. Grass-eating mammals, like zebras and antelope, are key players in this ecosystem. Their grazing practices not only control the growth of grasses, preventing dominance of any one species but also create a patchwork of habitats. This promotes biodiversity, which is essential for the resilience of the ecosystem as a whole. Predatory animals, such as lions and hyenas, in turn, depend on these herbivores for sustenance, completing a vital ecological circle.

The rainfall of the savanna is not just a climatic condition; it is a crucial determinant of the ecosystem’s health. Variability in precipitation influences the timing of flowering and breeding cycles among animal populations. Many species synchronize their reproductive activities with the wet season to ensure the survival of their young, capitalizing on an abundance of resources when conditions are most favorable. Consequently, a failure of rainfall patterns—due to climatic anomalies or human-induced changes—can have catastrophic effects on local wildlife populations.

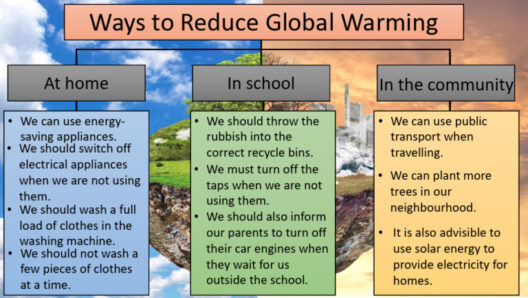

Climate change is a pressing concern for the savanna ecosystem. Alterations in weather patterns, driven by global warming, threaten to disrupt the balance of this unique biome. Extended droughts can lead to habitat degradation, which in turn endangers the myriad species interconnected within the savanna’s web of life. Furthermore, increased temperatures may shift the distribution of plant species, allowing for invasive flora to encroach upon traditional habitats, potentially displacing native varieties that are essential for regional biodiversity.

The savanna climate also has repercussions for human communities living in or around these ecosystems. Many indigenous populations rely on the resources provided by the savanna, whether through traditional agriculture, livestock grazing, or artisanal fishing. However, as climate patterns shift, these communities face challenges in sustaining their livelihoods. Erratic rainfall can result in food insecurity, leading to social and economic strain. Efforts to promote sustainable land-use practices are vital in safeguarding both human and ecological interests.

In conclusion, the savanna represents a climate that harmonizes life’s resilience and dependence on cyclical patterns of rain and drought. The flora and fauna that inhabit this biome have evolved in magnificent ways to adapt to its climatic nuances. However, as the specter of climate change looms larger, the stability of this ecosystem hangs precariously in the balance. Understanding and advocating for responsible stewardship of savanna landscapes is crucial not only for biodiversity but also for the well-being of the human communities that depend upon them. The savanna is more than just a picturesque landscape; it is a research hub, a livelihood, and a beacon of resilience in the face of climatic variability.