The climate of the Southwest United States is a fascinating amalgamation of various meteorological phenomena, characterized by significant variability due to its unique geography and diverse topography. This region, spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and California, exhibits features predominantly associated with desert environments, while also accommodating extraordinary mountainous ecosystems. Understanding the climate of the Southwest requires a detailed examination of both desert dryness and mountain weather.

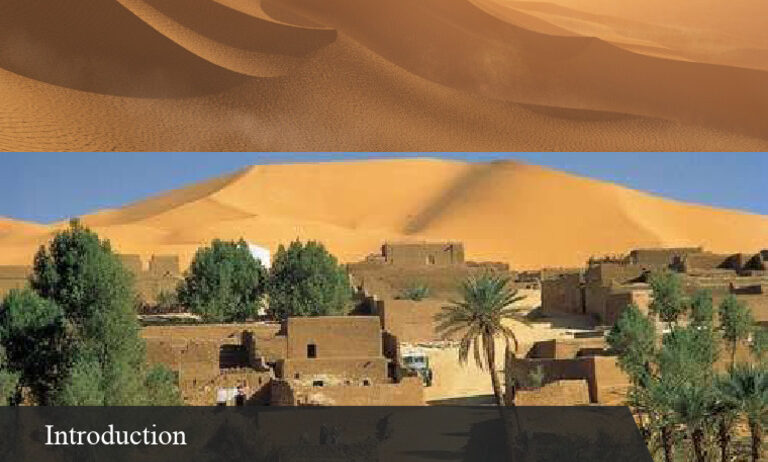

Desert climates, often classified under the Köppen climate classification as BWh (hot desert) and BWk (cold desert), are dictated by low precipitation levels, extreme temperature variations, and high evaporation rates. Rainfall is scant, averaging less than ten inches annually in many locations. This scarcity, coupled with insolation that can elevate temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit during summer months, engenders a quintessential arid desert landscape. The Sonoran Desert and the Mojave Desert exemplify this classification, where flora and fauna have adapted masterfully to endure such rigors.

Despite the pervasive dryness, the Southwest’s climate is not exceedingly monotonous. It showcases an array of desert types, each with distinctive characteristics. The Great Basin Desert, for instance, is known for its cold desert type, receiving slightly more precipitation than its hotter counterparts, fostering a unique collection of vegetation and wildlife. Conversely, the Sonoran Desert, with its iconic saguaro cacti, thrives in conditions fostered by both summer monsoons and winter precipitation, creating a dynamic habitat that supports diverse biological life.

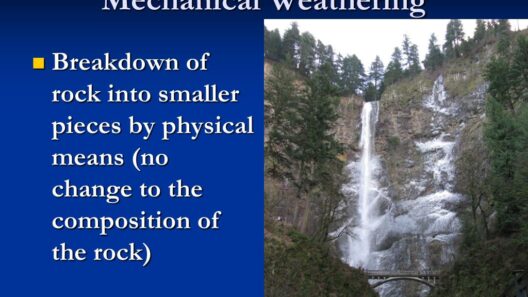

Transitioning from vast stretches of arid landscapes, one encounters dramatic mountain ranges. The Rockies and Sierra Nevada rise majestically against the skyline, presenting stark contrasts in climate. Elevation plays a pivotal role in influencing weather patterns. As altitude increases, temperatures decrease, and precipitation patterns shift significantly. Mountainous areas can experience heavy snowfall in winter, creating vital water resources through melting snowpack during warmer months, essential for agriculture and urban water supplies.

In the Sierra Nevada, for example, the climate can vary dramatically within just a few miles. The western slopes, facing the Pacific Ocean, benefit from moist air masses that give rise to lush coniferous forests, bustling with biodiversity. In juxtaposition, the eastern slopes transition swiftly to semi-arid conditions, ultimately meeting the vast expanses of the Great Basin Desert. Such climatic gradients underscore the profound relationship between topography and weather patterns in the Southwest.

One cannot overlook the phenomenon of monsoons which drastically alters the climatic landscape during the summer months. From late June through September, the Southwest experiences a significant uptick in humidity and precipitation, a respite from the aridity that predominates. These monsoonal storms often culminate in brief, intense showers, accompanied by thunder and lightning, revitalizing parched ecosystems. They play a crucial role in the hydrological cycle, replenishing surface water and groundwater reserves, and supporting the growth of seasonal vegetation.

Climate variations are also intrinsically linked to human activities, whose impacts can exacerbate the already precarious balance of natural systems. Urbanization in areas like Phoenix and Las Vegas has led to the urban heat island effect, where metropolitan areas suffer from elevated temperatures, altering local weather patterns. Increased water demands further strain resources, leading to a concerning decline in both surface water supplies and groundwater levels.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity to the environmental tapestry of the Southwest. Projections indicate that temperatures in this region may rise significantly in the coming decades, with shifts in precipitation patterns that could render some areas more susceptible to drought. The implications for biodiversity, agriculture, and water management are profound. Ecosystems already stressed by anthropogenic influences may face compounded challenges, threatening species extirpation and altering habitat viability.

Water scarcity remains one of the most pressing issues confronting the Southwest. The combination of burgeoning populations and diminishing water resources puts immense pressure on water availability in a region already marked by aridity. The Colorado River, a vital artery for agriculture and domestic usage, has seen diminishing flow levels, leading to contentious debates over water rights and usage. Implementing sustainable water management practices is vital to addressing these challenges while safeguarding the natural ecosystems associated with these vital waterways.

Moreover, understanding the interrelationship between climate, geography, and humans necessitates a collaborative approach. Stakeholders, including local governments, indigenous communities, and environmental organizations, need to engage in meaningful dialogues to chart a sustainable future for the region. Conservation efforts aimed at preserving ecosystems, alongside innovative agricultural practices to maximize water efficiency, can lead to resilience in the face of climatic vicissitudes.

In conclusion, the climate of the Southwest is an intricate tapestry woven from the threads of desert dryness and mountainous variability. The ongoing interactions between these diverse climates are continually shaped by natural forces and human impacts. Addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by climate change, water scarcity, and habitat preservation will require collective action and a commitment to sustainable practices. By fostering a deeper understanding of this region’s climate dynamics, stakeholders can work towards ensuring a balanced coexistence with the natural environment, ultimately benefiting both ecosystems and communities alike.