The tundra climate is often characterized by its cold temperatures, sparse vegetation, and unique ecological dynamics. This biome presents one of the harshest habitats on Earth, yet it also supports a range of life forms that have adapted to its extreme conditions. Understanding the tundra climate is not merely an academic exercise; it offers profound insights into the resilience of nature and the implications of climate change on these fragile ecosystems.

At its core, the tundra is defined by its climatic conditions, which feature long, frigid winters and short, cool summers. Generally, the average annual temperature in tundra regions hovers around −12 to −6 degrees Celsius (10 to 21 degrees Fahrenheit). The summer months bring a slight reprieve, with temperatures occasionally rising above freezing, yet the growing season remains critically short, averaging only about 50 to 60 days. This limited timeframe dictates the life cycles of flora and fauna, creating a unique set of ecological relationships.

Two main types of tundra exist: Arctic tundra and Alpine tundra. Arctic tundra, found in regions near the North Pole, is more expansive and characterized by its permafrost, a permanently frozen layer beneath the surface. This permafrost significantly affects hydrology, as it prevents water from infiltrating the ground, leading to the formation of wetlands and shallow lakes during the brief summer thaw. In contrast, Alpine tundra occurs at high altitudes, such as mountain tops, where temperature and atmospheric pressure contribute to its cooler climate, despite being farther from the poles.

The flora in tundra regions is predominantly low-growing and hardy. It comprises mosses, lichens, low shrubs, and grasses, all of which have evolved adaptations to thrive in low-nutrient soils and extreme temperatures. The root systems of these plants are typically shallow, allowing them to absorb moisture quickly during the fleeting periods of thaw. Additionally, during the brief summer, the tundra is painted with vibrant colors, as various species bloom in response to the extended daylight hours, a phenomenon caused by the Earth’s axial tilt during summer months.

Fauna in tundra ecosystems exhibit remarkable adaptations to survive the harsh conditions. Many species engage in migratory behaviors to exploit food resources, nesting grounds, and milder weather. Birds such as the Arctic tern travel thousands of kilometers to exploit the summer influx of insects, while mammals like caribou and polar bears have evolved physiological and behavioral traits that enable them to endure the bitter cold. The insulating properties of thick fur and blubber allow these animals to maintain their body heat, while camouflage plays a critical role in predator-prey interactions.

When thinking of survival in such an inhospitable environment, there exists a common observation: life is exquisitely interwoven with the elements. Organisms in the tundra exhibit a symbiotic relationship with their habitat, reflecting a finely-tuned balance that has persisted over millennia. The relationship between plant life—a fundamental component of the tundra’s food web—and herbivorous species exemplifies this. Herbivores depend on the sparse vegetation during the short summer, while, in turn, they serve as a vital food source for predators, completing an intricate ecological cycle.

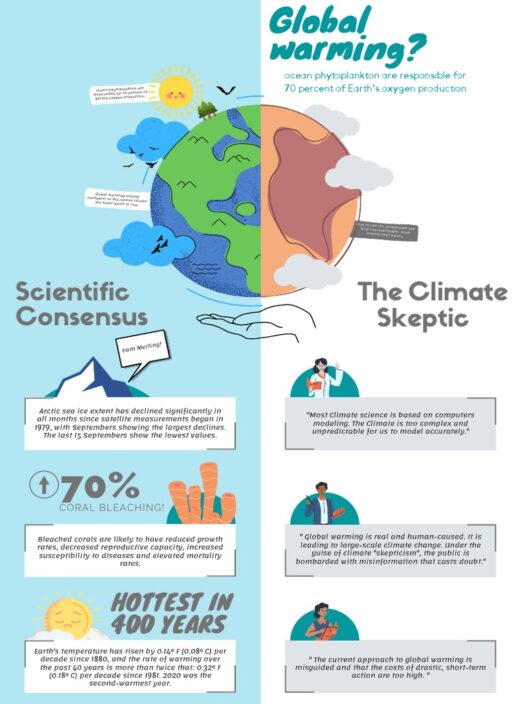

Despite its seemingly inhospitable nature, the tundra is a critical component of the global ecosystem. It acts as a carbon sink, sequestering immense quantities of carbon dioxide in the permafrost. However, rising global temperatures posing the threat of permafrost thawing can release this carbon back into the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change. This phenomenon raises concerns not just for the tundra’s flora and fauna, but for the planet’s climate system as a whole. The precarious balance in tundra ecosystems is becoming increasingly endangered, and monitoring these changes is essential for understanding broader environmental shifts.

In addition to its ecological importance, the tundra holds cultural significance for indigenous communities who have long inhabited these regions. These groups possess extensive knowledge of the land, including how to navigate its challenges and utilize its resources sustainably. Their traditions and practices are deeply connected to the rhythms of the tundra, emphasizing a profound respect for nature and a commitment to preserving this delicate environment. As climate change threatens the integrity of these ecosystems, the wisdom of indigenous peoples becomes invaluable for guiding conservation efforts and fostering resilience.

The fascination with tundra climates often stems from their paradoxical nature: they are both starkly beautiful and alarmingly fragile. The mesmerizing landscapes, with their endless horizons and dramatic wildlife, invoke a sense of wonder. Yet, this same beauty conceals vulnerabilities that demand our attention. As stewards of the planet, we must recognize the intrinsic value of these ecosystems not only for their biodiversity but also for their contributions to global ecological health.

Understanding tundra climates is imperative as we strive to combat the multifaceted challenges posed by climate change. As temperatures rise and weather patterns become increasingly erratic, the tundra serves as a litmus test for the health of our planet. Moving forward, fostering awareness about these ecosystems, advocating for their protection, and supporting sustainable practices will play a crucial role in ensuring that the tundra and its inhabitants continue to thrive for generations to come. Ultimately, the survival of the tundra is not just a matter of ecological concern; it reflects our relationship with nature and our responsibility to safeguard its integrity.