Understanding the timeline of climate change discovery is pivotal in grasping the urgency of climate action. This scientific journey has evolved over centuries, giving us insight into how humanity’s activities influence the environment and the planet’s changing climate. Below, we explore the significant milestones that have marked the discovery and understanding of climate change.

Before we delve into the scientific timeline, it is essential to understand the fundamental concepts surrounding climate change. It involves long-term alterations in temperature and typical weather patterns in a place. While climate change as a natural phenomenon has occurred throughout Earth’s history, the contemporary concern arises from anthropogenic—human-induced—changes that began in the Industrial Revolution. This article will navigate through time to unearth when climate change was first recognized and how scientific understanding has evolved.

The Enlightenment Era: Early Theories on Climate

The roots of climate change discovery can be traced back to the Enlightenment Era in the 18th century. During this period, scientists began to systematically study natural phenomena. One pivotal figure was John Tyndall, an Irish physicist, who in 1859 experimented with gases in the atmosphere. He discovered that certain gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, can trap heat. This research laid the groundwork for understanding the greenhouse effect, a crucial concept in the study of climate change. Tyndall’s findings illuminated how gases in Earth’s atmosphere contribute to global temperatures, foreshadowing future discussions around climate change.

From the mid-19th century onward, the industrial transformation accelerated. The burning of fossil fuels released unprecedented amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, prompting early observations regarding temperature increases—a precursor to climate change’s contemporary discourse. Historians often look to the year 1896 as a pivotal benchmark, marking the publication of Svante Arrhenius’s theory. His calculations suggested that doubling carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could raise global temperatures by about 5 to 6 degrees Celsius, indicating a profound alteration in climate systems due to human actions.

The Early 20th Century: Discerning Patterns

As the 20th century unfolded, scientists began to accumulate empirical data regarding the Earth’s climate. In the 1930s, British engineer Guy Stewart Callendar published compelling evidence showing that global temperatures were indeed rising. He correlated these temperature changes with increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, a notable moment linking industrial activities to climate change. His findings stirred the scientific community and raised concerns about potential long-term ramifications for the planet.

However, skepticism regarding climate change remained prevalent in scientific circles. The assertion that present warming trends were linked to human activity continued to face challenges until the latter half of the century when foundational studies emerged. The 1950s marked a significant turning point with the establishment of the Mauna Loa Observatory, where continuous measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide began. The Keeling Curve illustrated an unmistakable upward trend in CO2 concentrations, firmly substantiating earlier hypotheses about the greenhouse effect and its link to human activities.

The 1980s and 1990s: A Convergence of Evidence

The 1980s witnessed an increasing scientific consensus on climate change. This decade was marked by significant reports highlighting the potential consequences of global warming. In 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established, combining the expertise of thousands of scientists globally to assess climate change’s risks, impacts, and policy responses. The IPCC’s reports provided critical evidence, bringing together multidisciplinary research on climate modeling and global temperature trends, further solidifying the link between greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

By the 1990s, comprehensive studies highlighted alarming patterns in global warming, ice cap melting, and extreme weather events. The second IPCC assessment report, released in 1995, stated that “the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” This declaration was a watershed moment, as it signaled unequivocal support within the scientific community regarding the human contribution to climate change.

The Contemporary Era: Urgency and Action

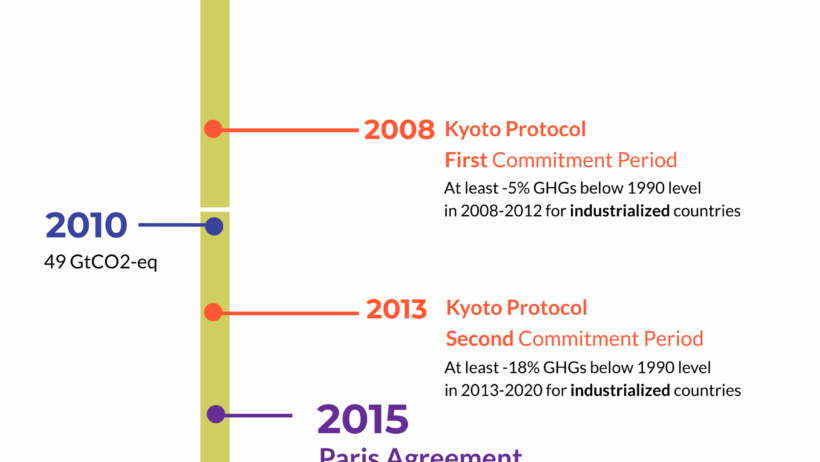

As we entered the 21st century, the climate change narrative shifted towards urgency. The IPCC continued to produce pivotal assessments, with the fourth report in 2007 stating that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal.” This sentiment inspired international discussions, leading to agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol and later the Paris Agreement in 2015, where nations committed to reducing carbon emissions to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Recent years have been marked by an increasing frequency of climate-related disasters, making it incumbent upon scientists to enhance their dialogue with policymakers and the public. Climate change is no longer a distant concern; it impacts economies, health, and biodiversity. As climate change science continues to evolve, its complexities, such as feedback loops and tipping points, reveal that addressing this global issue requires urgent and coordinated efforts.

As we reflect on the timeline of climate change discovery, it is important to acknowledge that understanding is still evolving. Researchers are now investigating the implications of climate change on various ecological and human systems, emphasizing that the scientific community’s work is integral to shaping effective climate policies. The historical context of climate change discovery underscores a broader call to action: as inhabitants of Earth, collective responsibility and awareness are paramount in confronting one of the most critical challenges of our time. The time to act is now, for the evidence is irrefutable, and the need for sustainable practices is more pressing than ever.