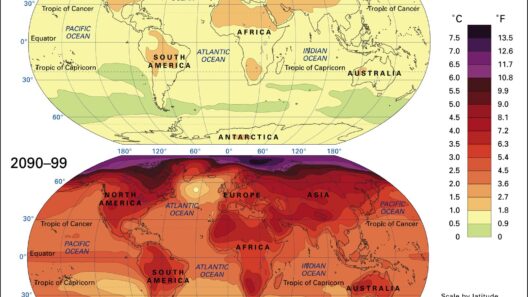

The Paris Climate Agreement represents a landmark accord that unites the global community in the fight against climate change. One might ask, “Who bears the financial brunt of this ambitious commitment?” As nations delineate their climate action plans—known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—the question of funding becomes pivotal. Thus, the dynamics of financial contributions and responsibilities in this intricate tapestry require thorough exploration.

At its core, the Paris Agreement is founded upon a principle of equity and shared responsibility. Developed countries, often referred to as Annex I countries, are expected to lead the charge in terms of funding and technical assistance. Why is that, you ask? These nations have historically contributed the lion’s share of greenhouse gas emissions. Their wealth allows them to catalyze sustainable technology and investment flows, ultimately transforming their economies while aiding emerging economies. As the adage goes, “Those who have the means to act must bear the weight.”

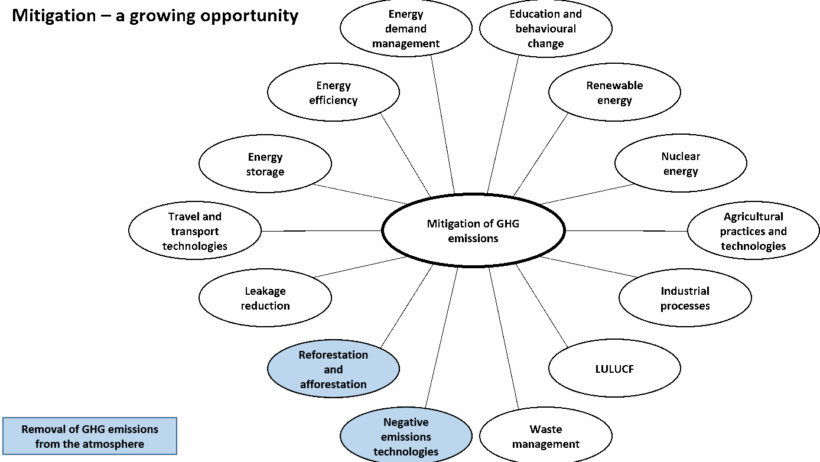

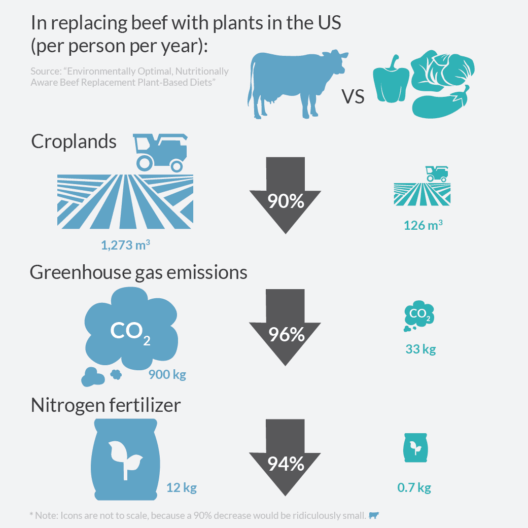

Nonetheless, it is essential to observe that the commitment to climate financing does not fall solely on the shoulders of developed countries. Emerging economies, despite not holding the same historical culpability for climate change, are also gradually entering the fray as significant players in the funding landscape. As these nations evolve, they are increasingly expected to contribute towards the collective endeavors of climate adaption and mitigation.

A central pillar of the funding structure is the Green Climate Fund (GCF), established to assist developing countries in their quest to combat climate change and adapt their economies. The GCF operates with a vision to channel $100 billion annually by 2020, a figure that reflects the scale of investment required to drive meaningful change. However, achieving this goal poses a formidable challenge, as national contributions often fluctuate based on domestic priorities and political will. Will countries meet their pledges, or will the fund resemble an empty coffers narrative?

Moreover, it is crucial to comprehend the mechanisms through which these funds are mobilized. Apart from direct contributions by governments, a multitude of financing modalities exist. The private sector serves as a vital source of funding, offering innovative solutions, technologies, and capital. Public-private partnerships are increasingly recognized as pivotal for harnessing private investment for sustainable projects. But here arises an intriguing challenge: how can the integrity of climate initiatives be safeguarded when profit motives creep into the equation?

Multilateral development banks (MDBs), such as the World Bank and regional banks, play a complementary role in providing finance and technical assistance. They are instrumental in ensuring projects meet not only ecological but also social and economic criteria. Still, the question remains: can these financing institutions navigate the delicate balance between developmental goals and profitability without compromising environmental integrity?

In addition to governmental efforts and private sector contributions, climate financing also hinges on innovative fiscal instruments. Carbon pricing schemes, such as taxes and cap-and-trade systems, can generate vital revenue that can be directed towards climate initiatives. By putting a price on carbon emissions, these strategies encourage reductions in greenhouse gas outputs and generate funding for sustainable development projects. Yet, could the potential backlash from industries that see these measures as burdensome impede progress?

International financial cooperation unfolds as another layer of complexity in the funding breakdown of the Paris Agreement. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) facilitates platforms where nations can collaborate and discuss climate finance, sharing experiences and best practices. This multilateral approach encourages engagement from all countries, but it also raises the question of accountability: how can nations ensure that funds are appropriated aptly and without corruption?

Notable too is the role of philanthropic organizations and foundations, which have a growing presence in climate finance. These entities often provide grants or investments to stimulate innovation and support projects that might be perceived as too risky by traditional investors. As they venture into this territory, one must wonder: does reliance on philanthropic funding foster sustainability, or does it instead risk creating a dependency that undermines long-term resilience?

Over the years, the necessity for transparency and inclusivity in climate finance has become increasingly pronounced. Initiatives such as the Climate Finance Delivery Plan aim to delineate pathways for guiding finance toward those who need it most. Enhanced reporting frameworks and commitment to open data will help bridge gaps and foster trust among stakeholders. However, with the stakes being extraordinarily high, can collaboration between governments, the private sector, and civil society coexist without friction?

As we navigate the pathway ahead, the question lingers: Who ultimately pays for the Paris Climate Agreement? The answer is a symphony of varied contributions—governments, businesses, civil society, and international organizations—all rendered in varying degrees. Each entity holds a part of the responsibility. The challenge lies not only in mobilizing the financial resources but also in ensuring that they are utilized effectively to produce tangible results, leading to a sustainable future for all.

Ultimately, confronting climate change demands unwavering commitment and innovation from all sectors of society. Financing the Paris Agreement is just the first step. The real test resides in fostering collaboration, ensuring accountability, and nurturing resilience in an era marked by environmental uncertainty. It will require ingenuity, unyielding resolve, and a clear understanding that the burdens of climate change must not fall disproportionately on the least responsible or most vulnerable. As we forge ahead, each contribution, whether large or small, manifests our collective commitment to the planet and future generations.