The Paris Climate Agreement, adopted in 2015, has become a pivotal framework in the global effort to combat climate change. It was conceived to unite countries in a collective endeavor to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, with aspirational goals of restraining the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The accord has garnered widespread support, with nearly every nation in the world ratifying it. However, a handful of countries have notably abstained from joining. Understanding who these nations are and the reasons behind their exclusion provides valuable insight into the complexities surrounding global climate politics.

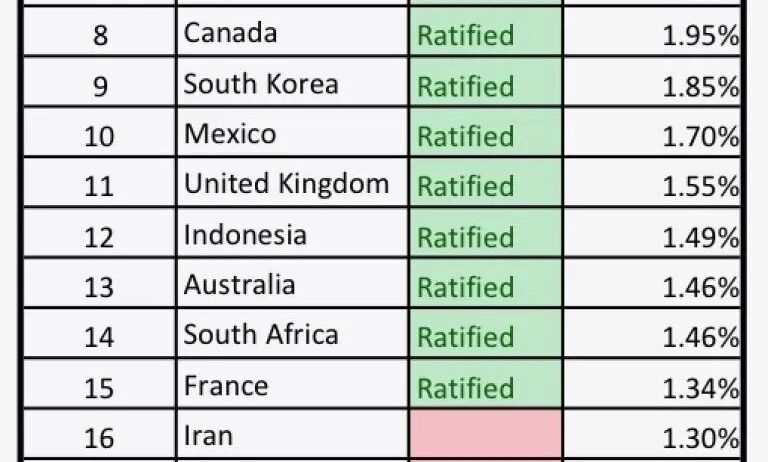

Currently, three nations have formally indicated their withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: the United States, Turkey, and Iran. The United States, under former President Donald Trump, made headlines in 2017 when it announced its decision to withdraw, claiming that the agreement disadvantaged the nation economically. However, this move sparked considerable criticism both domestically and internationally, leading to further discussions about the socio-economic implications of such an action. The Biden administration has since rejoined the Accord, signaling a commitment to re-engage with international climate initiatives.

Turkey’s hesitance to accede to the agreement stems from its desire to be recognized as a developing nation. This classification would entitle it to additional financial and technological support for climate programs. However, its significant greenhouse gas emissions and economic clout cast a shadow over its request. While Turkey continues to negotiate its status within the framework, its lack of commitment underscores the intricate balance between economic growth and environmental responsibility.

Iran’s situation is further complicated by geopolitical tensions and sanctions imposed by various nations, particularly the United States. As a major oil producer, Iran’s willingness to commit to stringent climate targets is hampered by a dual concern: the need for economic stability versus the urgency for environmental action. This dilemma resonates with many nations that rely heavily on fossil fuel exports, revealing the intricate interplay between economic interests and climate commitments.

Beyond these three nations, other countries exhibit a tacit reluctance to fully embrace the accord. For instance, Russia has participated in the agreement but often shows ambivalence regarding the implementation of substantial climate policies. Citing economic concerns and the need for energy security, Russia highlights an ongoing debate over balancing environmental commitments with national interests. This notion is prevalent across many emerging economies that prioritize development over immediate climate action.

Some smaller island nations and developing countries also perceive the Paris Agreement’s framework as inadequate to address the unique challenges they face. They argue that the mechanisms for financial support, technology transfer, and capacity building fall short of what is necessary to combat the repercussions of climate change that they experience on the frontlines. Their frustration with the agreement’s terms underscores the necessity for richer nations to fulfill their commitments, a sentiment echoed in numerous climate summits.

An overarching theme among these non-participating or hesitantly participating nations is the tension between development and environmental stewardship. Many countries fear that aggressive climate policies could stifle economic growth, exacerbate poverty, and hinder progress toward developmental goals. As global inequality persists, the dilemma is pronounced: how to elevate living standards without exacerbating the climate crisis.

Furthermore, a prevalent skepticism regarding the efficacy of international frameworks often clouds the discourse. Countries that have historically benefited from fossil fuel economies may question the fairness of the global demand for rapid transitions to renewable energy sources without first ensuring equitable development. This skepticism can lead to half-hearted engagements or outright refusals to fully commit to agreements like Paris.

To complicate matters, the political landscape in many regions fluctuates, influenced by populist sentiments and resistance to environmental regulations. Such political dynamics can lead to erratic climate policy stances that hinder consistent adherence to international agreements. For instance, a change in government may result in a reversal of previously agreed-upon climate commitments, fostering uncertainty in the global climate dialogue.

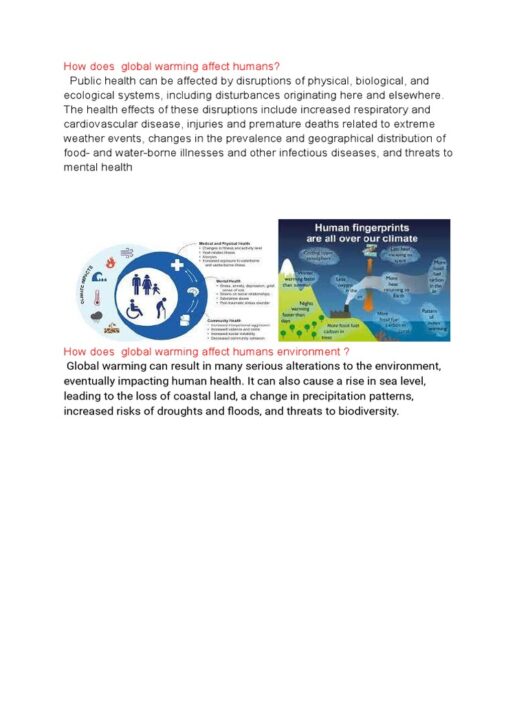

The path forward necessitates a nuanced understanding of these complexities. Climate action cannot exist in a vacuum; economic, social, and political realities must be acknowledged and addressed. Emerging nations often require substantial assistance in transitioning to greener economies, a commitment that wealthier nations must prioritize, moving beyond mere rhetoric into actionable support.

Moreover, fostering international collaboration initiated under platforms like the Paris Agreement relies heavily on transparency, mutual respect, and a willingness to understand diverse national contexts. Diplomatic efforts must delve deeper into the economic narratives and existential fears that underpin resistance to the agreement. By doing so, a pathway to inclusiveness and cooperative climate action can be forged.

In conclusion, while the Paris Climate Agreement stands as a landmark achievement in climate governance, the absence of certain countries exposes the chasms in achieving universal compliance. The skepticism, economic imperatives, and socio-political dynamics at play underline the necessity for a broader, more equitable approach to climate action. Moving forward, the global community must embrace the complexities of engagement and ensure that the urgent call to address climate change is matched by an equally compelling commitment to global equity and sustainable development.