In the realm of economics, particularly when considering a closed economy, a plethora of intriguing dynamics come into play. A closed economy is defined as one that does not partake in international trade; all economic activities occur within its own borders. To gain a cogent understanding, we must dissect the various components and implications of such a system.

First and foremost, let’s clarify the primary elements that constitute a closed economy. Here, we look at the key variables: Y, representing total output or Gross Domestic Product (GDP); C, indicative of consumer spending; I, denoting investment made by businesses; and G, which represents government expenditure. In a closed economy, the following equation is fundamental: Y = C + I + G. This equation embodies the essence of economic activity, delineating how total output is allocated among consumption, investment, and government spending.

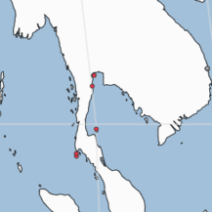

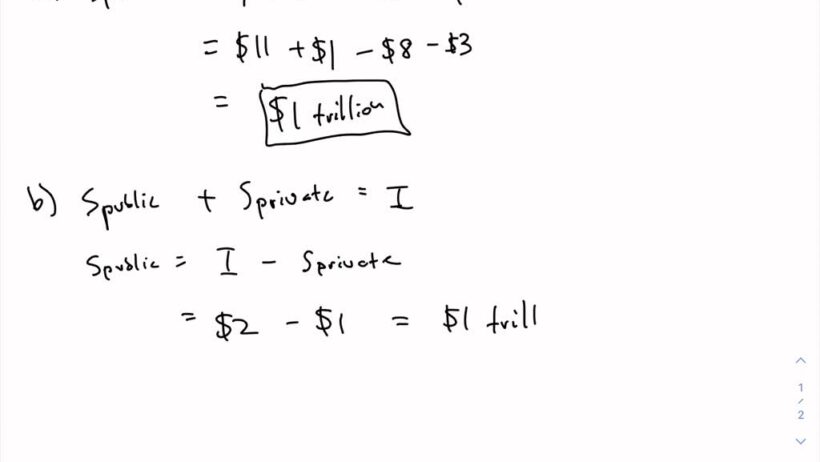

Another pivotal aspect to consider is the influence of savings within a closed economy. Savings, often seen as a financial reservoir, play a critical role. They reflect the portion of disposable income not allocated to immediate consumption. The equilibrium of the economy hinges on the interplay between savings and investments. In this context, the savings-investment identity emerges: what is saved must be invested in some form. Thus, one can decipher that greater savings can lead to increased investments, potentially bolstering economic growth.

Moreover, we must examine the ramifications of government spending within a closed economy. The government acts as a pivotal player, influencing overall economic activity via fiscal policy. Through expenditure, governments can stimulate demand—especially in times of recession—by initiating projects or investing in social programs. However, this expenditure is often financed through taxation or, in some scenarios, borrowing. Herein lies a conundrum: excessive government spending without corresponding tax revenue can lead to burgeoning deficits, prompting future economic ramifications.

The underpinning notion of aggregate demand also merits discussion. It aggregates the total demand for goods and services and is primarily composed of consumption, investment, and government spending. In a closed economy, aggregate demand must align with domestic output since external trade is negligible. When aggregate demand exceeds production capacity, the economy could encounter inflationary pressures, while a deficit could precipitate recessionary conditions.

We must not overlook the significance of economic cycles. Each closed economy endures fluctuations characterized by periods of expansion and contraction. Understanding these cycles is vital to discerning consumer behavior, business investment, and government policy responses. Typically, during an expansion, consumer confidence burgeons, leading to increased spending and investment. Conversely, in contractions, there’s a tendency for subdued consumption and tightening investments, which can adversely affect GDP.

Examining the closed economy also invites contemplation of market structures. The nature of these markets can vary—ranging from competitive to monopolistic systems. In competitive markets, prices are dictated by supply and demand dynamics. Alternatively, in monopolistic or oligopolistic scenarios, market power allows a few entities to dictate terms, potentially leading to inefficiencies within the economy.

Labor market dynamics are another critical component affecting the closed economy. Employment rates significantly influence consumption patterns. High employment generally correlates with greater disposable income, fostering higher consumer spending. Strikingly, a closed economy might experience specific labor market distortions due to the lack of international competition; labor could become less mobile, leading to inefficiencies in resource allocation.

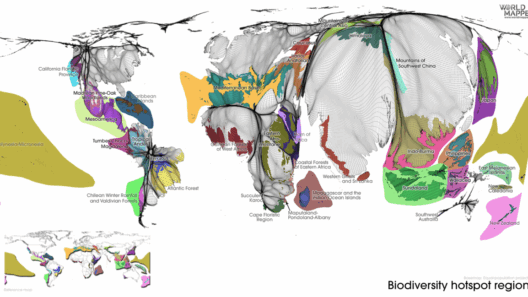

Additionally, environmental considerations must be integrated into discussions about closed economies, particularly in today’s ecological context. The ramifications of economic policies extend beyond mere numbers; they impact resource sustainability, pollution levels, and climate change. A closed economy limits the importation of goods, which can lead to over-reliance on domestic resources, heightening the risk of environmental degradation. Policy-makers must assess the long-term sustainability of their economic strategies while balancing short-term gains with ecological stewardship.

In a more speculative realm, one could ponder the potential for innovation within a closed economy. Without the pressures and influences of international competition, domestic industries may thrive under a protective umbrella. This environment could foster creativity and the development of new technologies. Conversely, the insulation from global trends might stifle innovation, as businesses may lack the impetus to advance if their market position is secure.

Ultimately, navigating through the intricacies of a closed economy reveals a tapestry rich with potential advantages and drawbacks. While the autonomy from foreign markets can cultivate self-reliance, it can equally lead to stagnation and vulnerability. As we reflect on various facets—be it government policy, labor dynamics, or environmental sustainability—we must recognize that a harmonious balance is pivotal to nurturing both robust economic growth and environmental health.

In sum, the landscape of a closed economy encapsulates a complex interplay of factors influencing its vitality. Understanding these elements can offer invaluable insights into the broader implications for society, ensuring that decisions made today bear fruitful outcomes for tomorrow. As such, grappling with these concepts empowers stakeholders to engage actively in fostering an economy that thrives within its boundaries while aspiring for sustainability.